Breaking Out:

Breaking Out:

—— The Taiwan New Wave

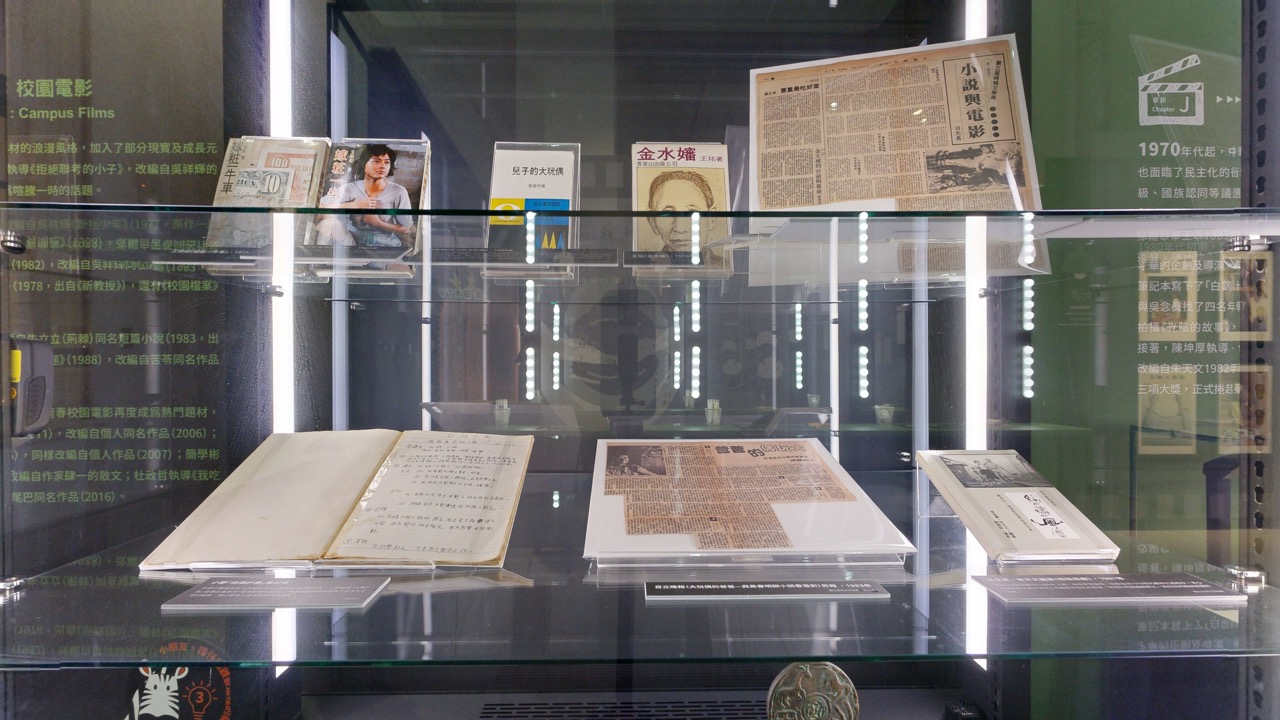

Aimless Youths: Campus Films

Aimless Youths: Campus Films

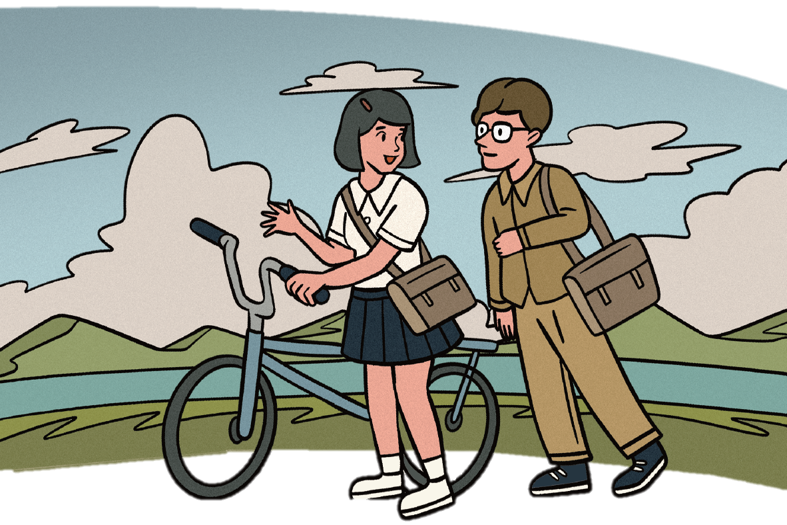

In the late 1970s, campus films followed Chiung Yao’s romantic style of school-themed stories while incorporating elements of reality and coming-of-age experiences, giving rise to a new cinematic genre. In 1979, Hsu Chin-liang directed The Boy Who Refused to Take the Entrance Exam, adapted from Brian Wu’s 1975 work of the same name, highlighting the flaws in the academic system and sparking widespread discussion.

Following this, Jack Lin directed A Problem Student in 1980, adapted from Brian Wu’s Juvenile Delinquency published in 1977; the original work was once banned by the Taiwan Garrison Command and forced to have a “bright” ending. Lin went on to direct a series of campus films, including Classmates in 1981, adapted from Wu Nien-chen’s screenplay; Taipei Sweet Heart in 1982, adapted from Brian Wu’s work of the same name published in 1981; An-An in 1984, adapted from Hsiao’s An-An’s Funeral pubished in 1978, from Professor Qi; and Campus Incidents in 1986, adapted from Ku Ling’s work of the same name published in 1985.

Additionally, Chiu Ming-cheng directed Edelweiss in 1987, adapted from Chu Lily’s short story of the same name, written under the pen name Thorn and taken from the 1983 collection Pumpkins Among Thorns; Peter Mak directed Sir, Tell Me Why in 1988, adapted from Ku Ling’s work of the same name, originally published in 1988.

In the 21st century, spurred by online novels and social media, youth campus films regained popularity. Examples include Giddens Ko’s You Are the Apple of My Eye in 2011, adapted from his 2006 novel; Neal Wu, whose real name is Wu Tzu-yun, directing At Cafe 6 in 2016, adapted from his 2007 work; Chien Hsueh-pin’s Do You Love Me As I Love You in 2020, adapted from Ssu Yi’s essay; and Ryan Tu’s My Best Friend's Breakfast in 2022, adapted from Misa’s 2016 work of the same name.

Nativist Literature and New Cinema

Nativist Literature and New Cinema

Since the 1970s, Taiwan has faced challenges in international diplomacy, and the party-state system underwent democratic pressures. Post-war youth began reflecting on issues of ethnicity, class, and national identity, questioning: “Who are we? Where do we belong? ”This gave rise to the “return to reality” mindset.

In the early 1980s, Ming Chi, general manager of Central Motion Picture Corporation, or CMPC, sought innovation by inviting young, talented planners and directors to revitalize the conservative studio. Hsiaoyeh quietly wrote in his notebook the “Our Time, Our Story” plan, symbolizing purity, courage, wisdom, reform, and takeoff, and, together with Wu Nien-chen, recruited four young directors - Tao Te-chen, Ko Yi-cheng, Edward Yang, and Chang I - to produce Time Story. Its break from conventional cinematic tropes unexpectedly captivated audiences. In 1982, Chen Kun-hou directed Growing Up, with a screenplay by Hou Hsiao-hsien and others, adapted from Chu Tien-wen’s “Love Story” contribution to the United Daily News. The film swept three awards at the Taipei Golden Horse Film Festival that year, officially launching the Taiwan New Cinema movement.

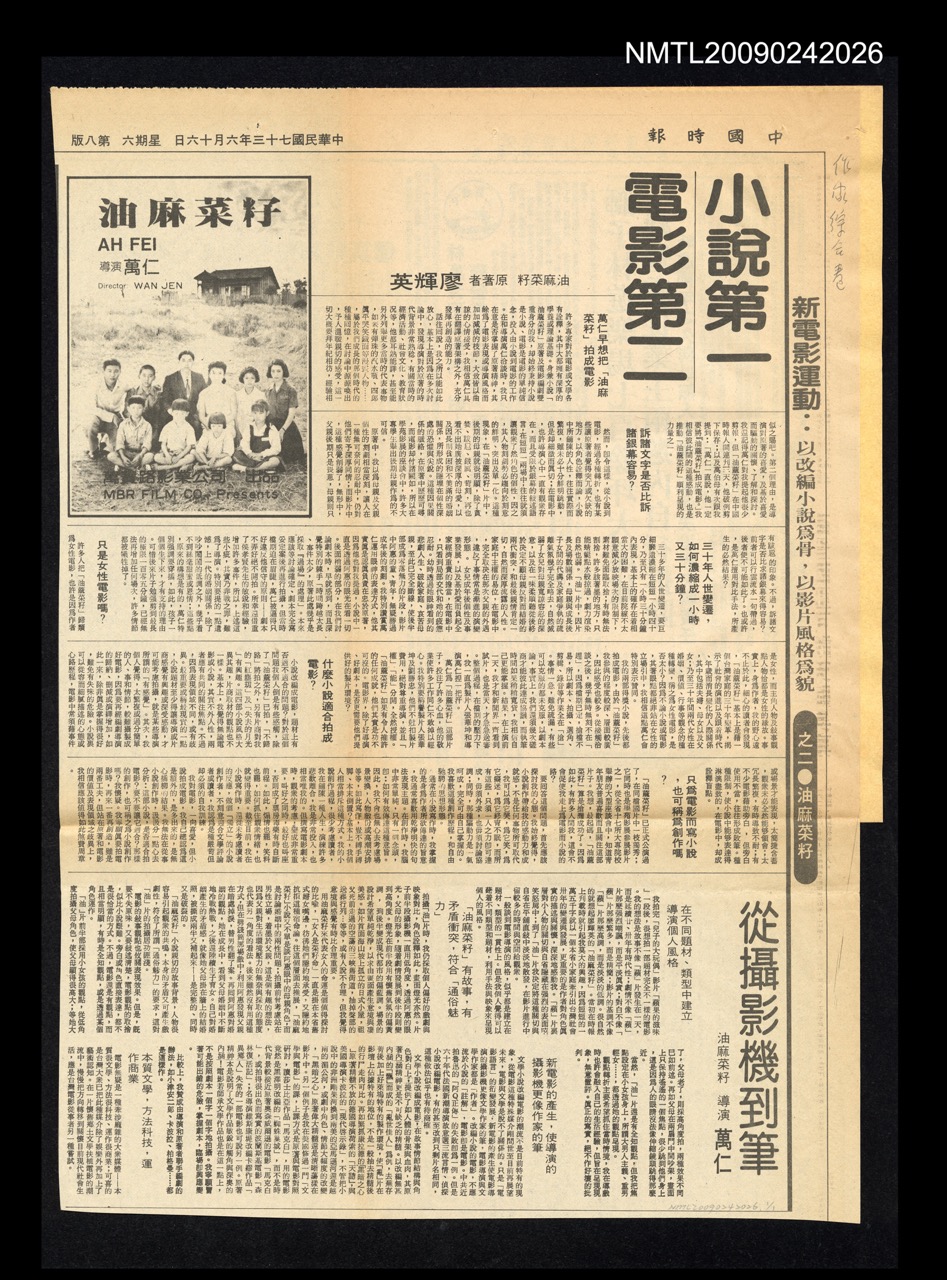

In 1983, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Wan Jen, and Tseng Chuang-hsiang respectively directed adaptations of Huang Chun-ming’s novels: "His Son's Big Doll", "The Taste of Apples", and "Vicki’s Hat", which were all published in 1969 as a collection, combined into the widely well-received triptych His Son's Big Doll.

Against the backdrop of the “return to reality” movement, New Cinema charged forward alongside literature, opening new frontlines in cultural expression and producing a large number of literary adaptations, particularly in the genre of "local literature". These included films such as Bye Bye, Goodbye, Rose, Rose, I Love You, Virgin Boy, Aunt Jinshui, The Dull Ice Flower, Marriage, and A Bird’s Cry, all of which were adapted from the works of Huang Chun-ming, Wang Chen-ho, Yang Ching-chu, Wang To, Chung Chao-cheng, Chi Teng-sheng, and Hsiao-lang (Huang Chung-hsiung).

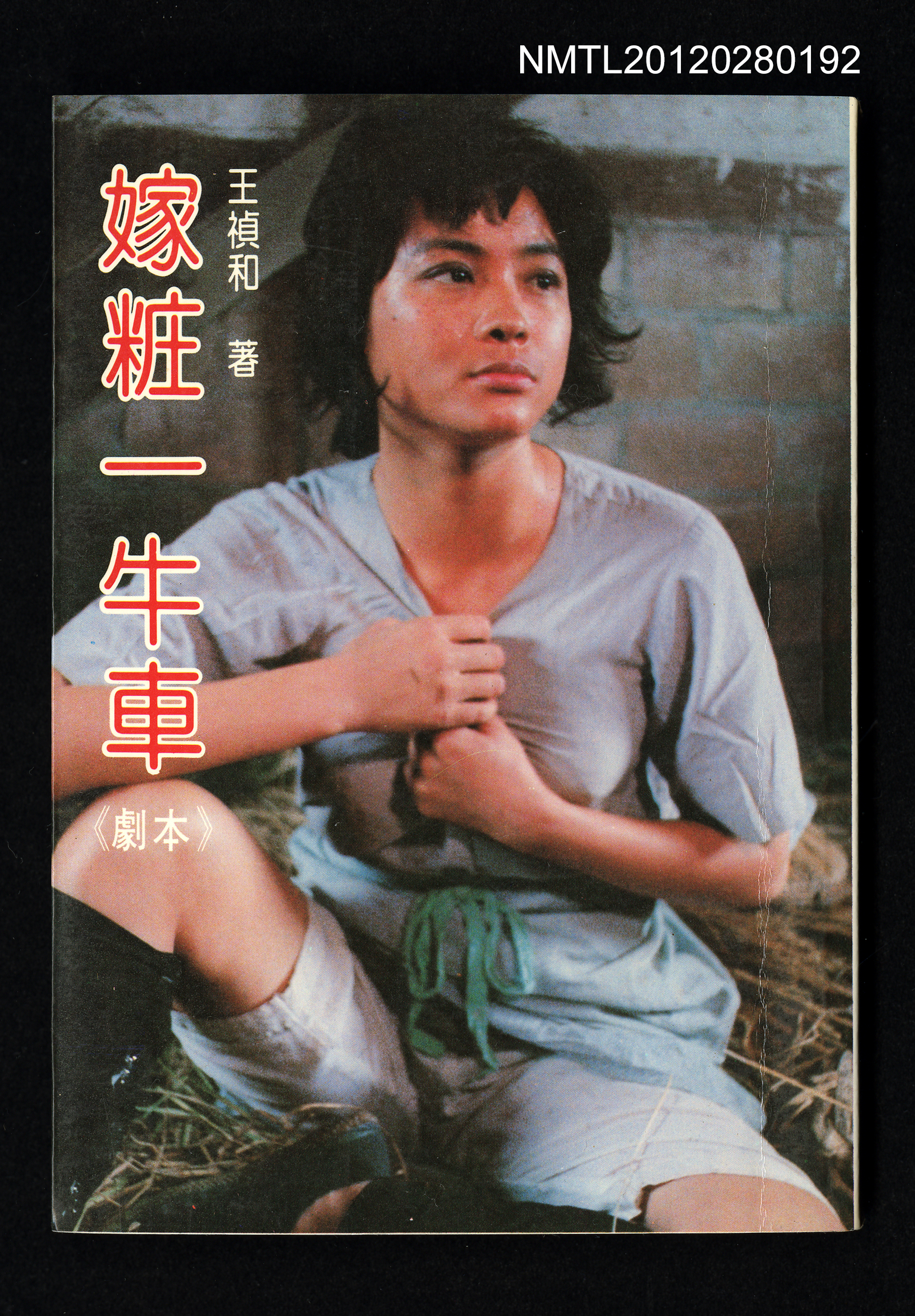

Wang Chen-ho The Oxcart for Dowry (Film Script, 1964) / Collection of The National Museum of Taiwan Literature

The story follows the protagonist Wan-fa, who, to avoid starvation, allows a wealthier man to live in his home,

creating an unspoken three-person cohabitation. Wang Chen-ho personally adapted the story into a film script in 1984, bringing it to the screen.

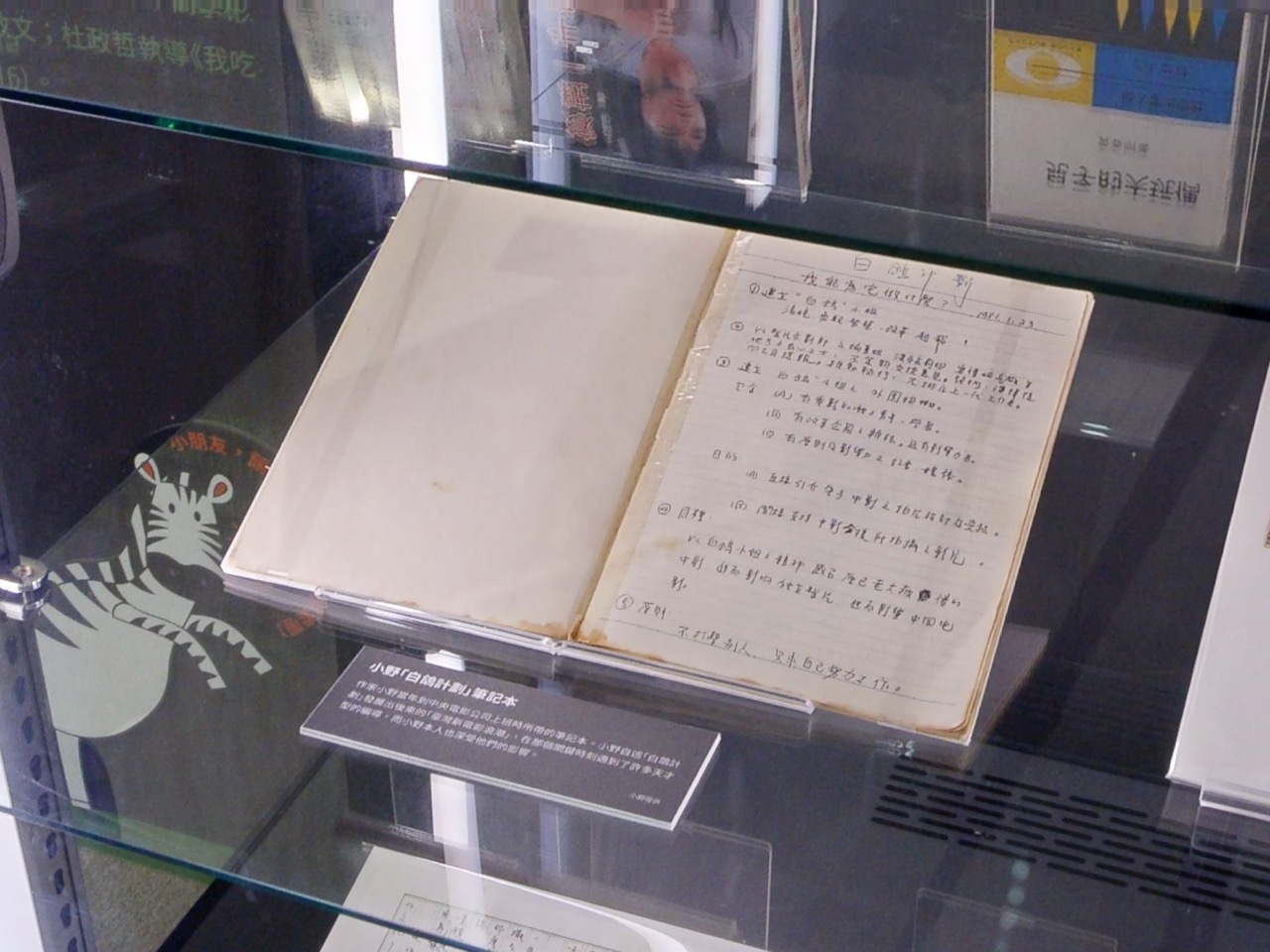

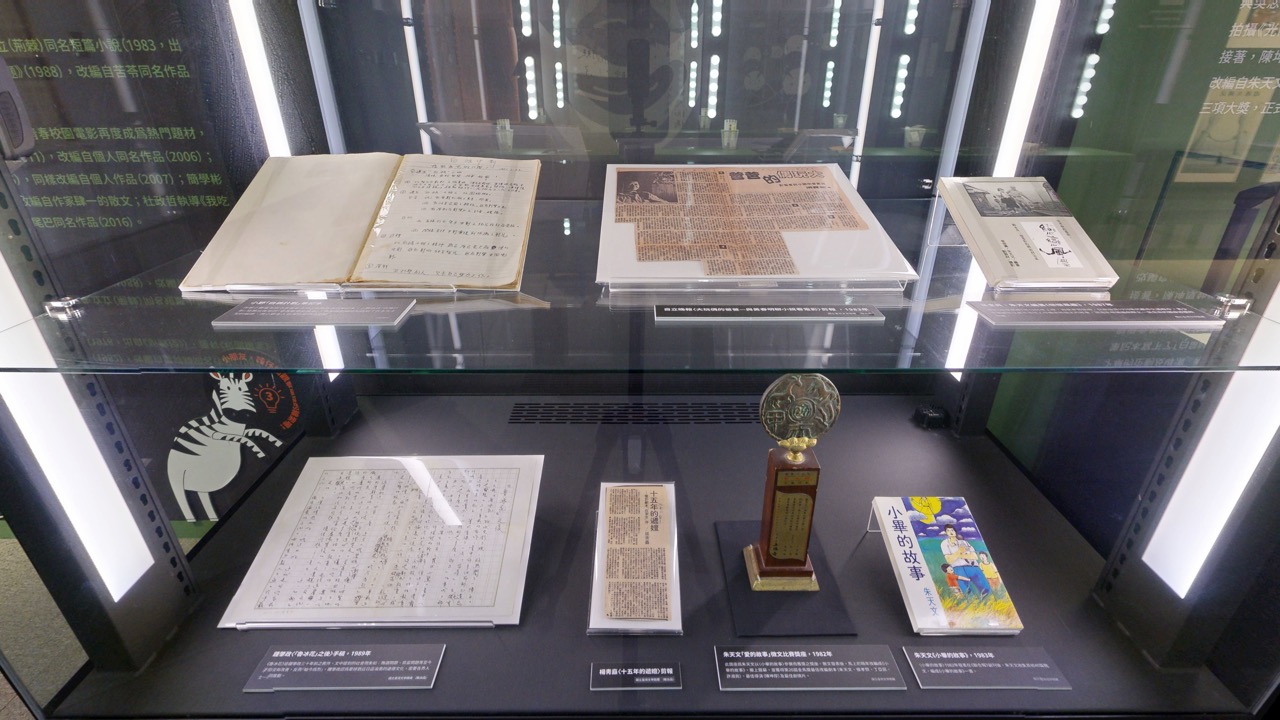

Hsiaoyeh’s Notebook White Dove Project / Our Time, Our Story / Courtesy of Hsiaoyeh

This notebook was brought by writer Hsiaoyeh during his time at Central Pictures Corporation.

Hsiaoyeh recalls that the Our Time, Our Story project later evolved into the Taiwanese New Cinema movement,

during which he encountered many talented directors who profoundly influenced him.

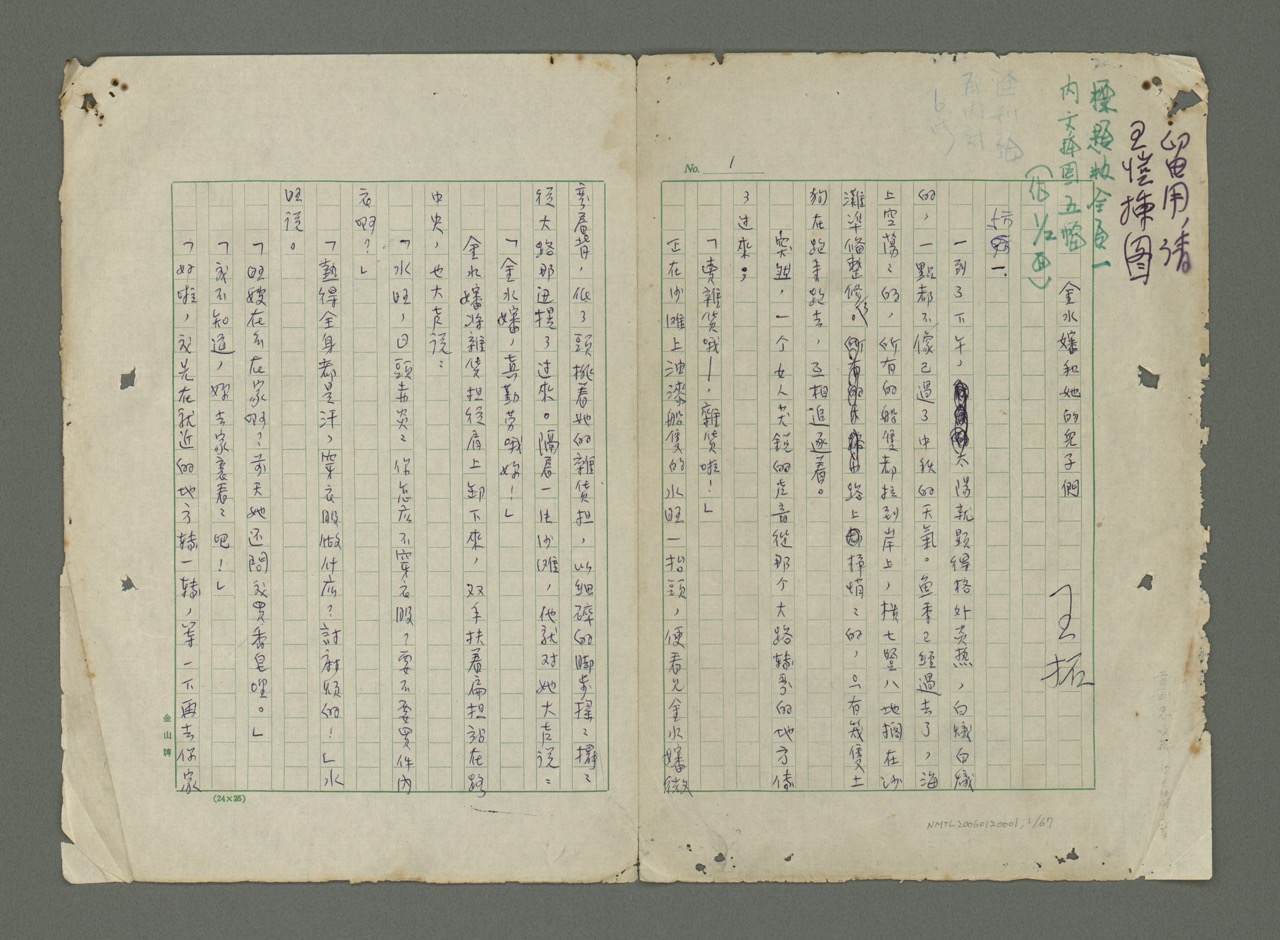

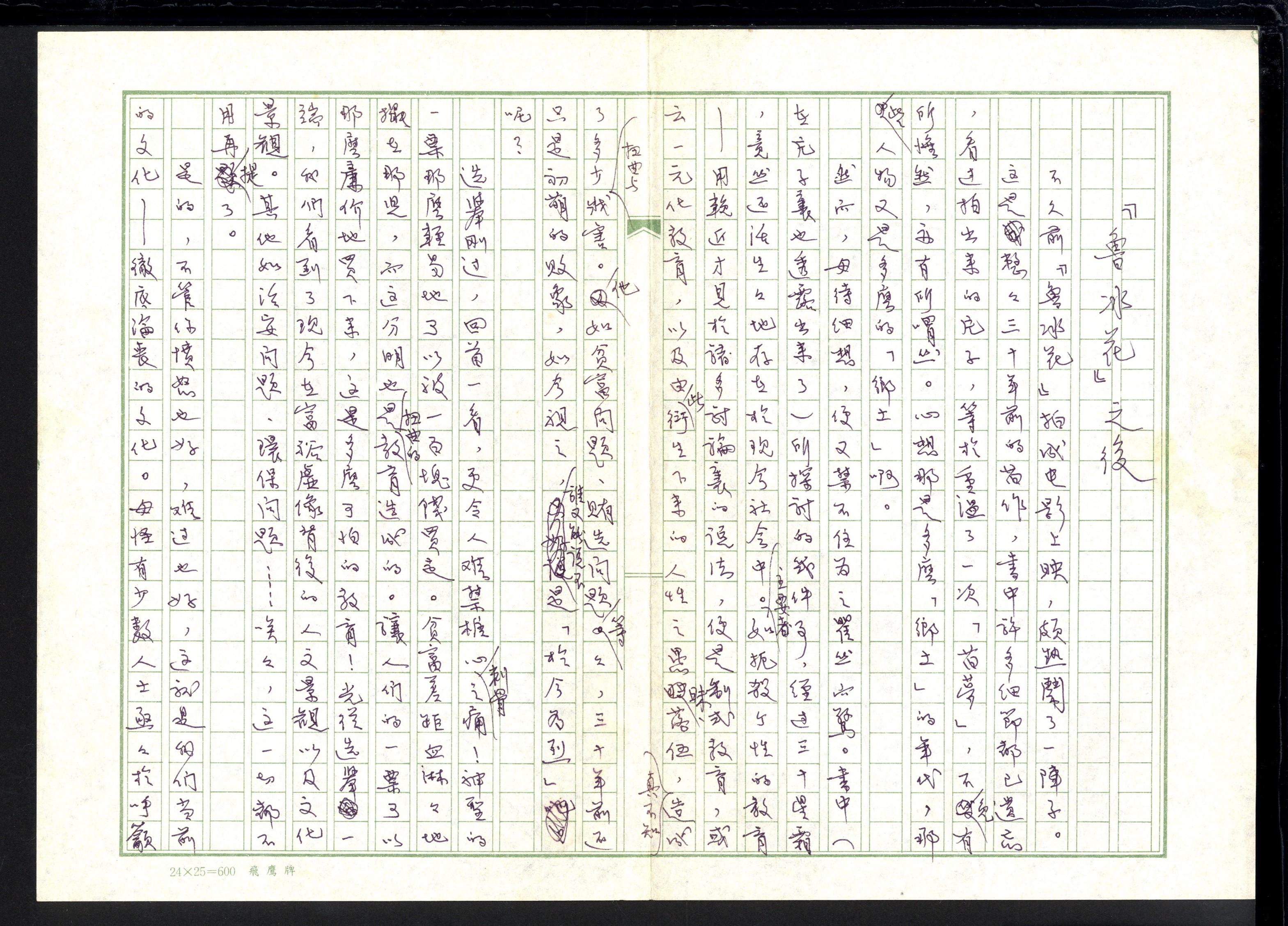

Wang To Aunt Jinshui and Her Sons (Manuscript, Date Unknown) / Collection of The National Museum of Taiwan Literature

Set in Wang To’s hometown of Badouzi Fishing Village in Keelung, the story centers on the protagonist Aunt Jinshui,

portraying the traditional image of Taiwanese women. Diligent, frugal, and hardworking,

Aunt Jinshui seeks her sons’ help to resolve a family financial crisis after they have established their own households.

However, she repeatedly encounters evasion, shirking of responsibility, and even harsh words from her sons and daughters-in-law.

Under the combined pressures of widowhood and debt collection fatigue, Aunt Jinshui ultimately resolves the debt problem through her own determination.

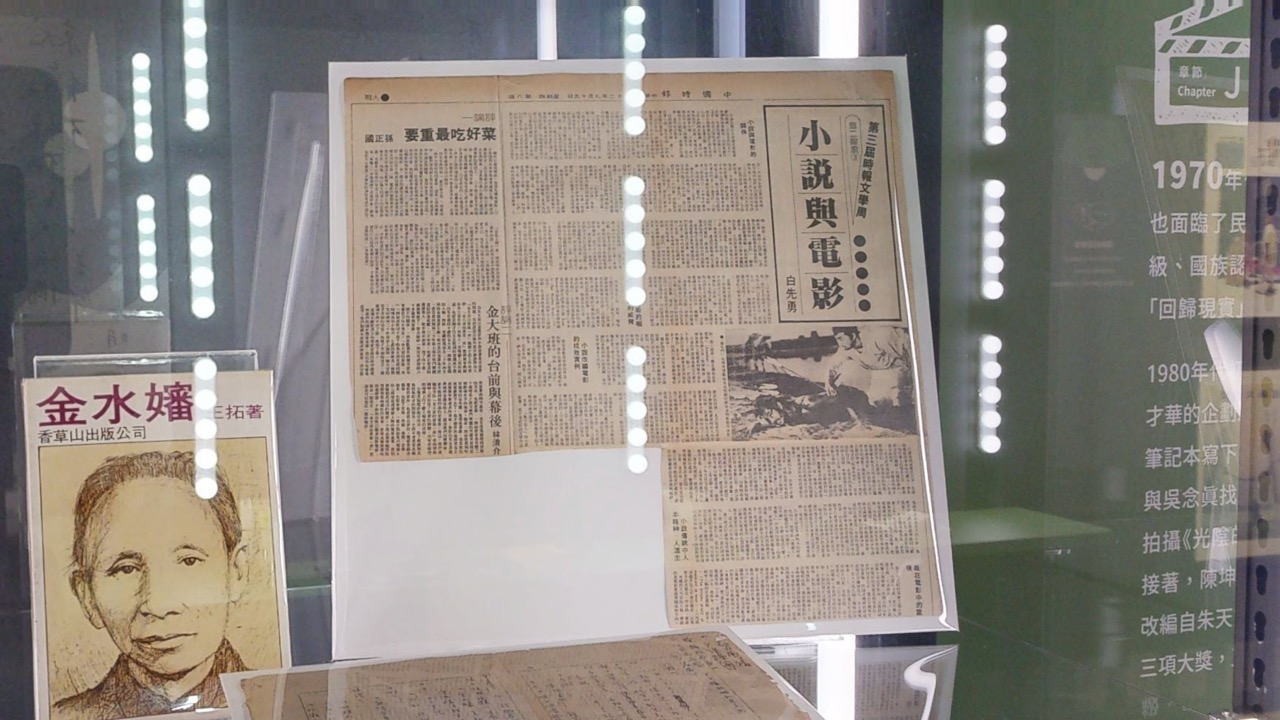

Writers Pai Hsien-yung's Clipping (1983) / Collection of The National Museum of Taiwan Literature

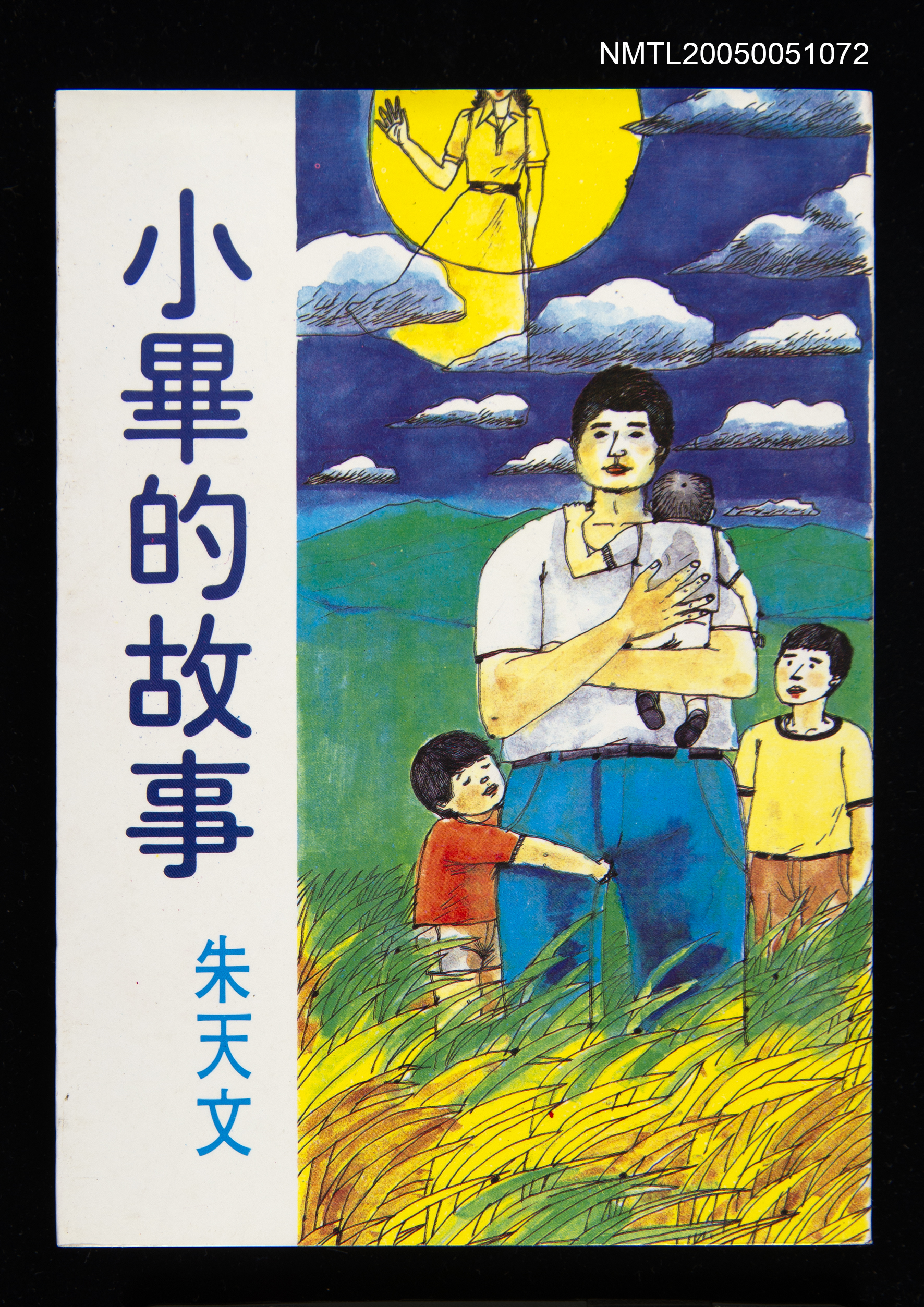

Chu Tien-wen Hsiao Bi’s Story, 1983 / Collection of The National Museum of Taiwan Literature

After the initial publication of Hsiao Bi’s Story in the United Daily News supplement in 1982,

Chu Tien-wen collected it with forty additional essays to compile this 1983 volume.

Chu Tien-wen Love Story Contest Trophy, 1982/ Collection of The National Museum of Taiwan Literature

This trophy was awarded to Chu Tien-wen for Hsiao Bi’s Story, which was adapted the following year into the film of the same name.

The film won the 20th Golden Horse Award for Best Adapted Screenplay (Chu Tien-wen, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Ting Ya-min, Hsu Shu-chen),

Best Director (Chen Kun-hou), and Best Narrative Feature.

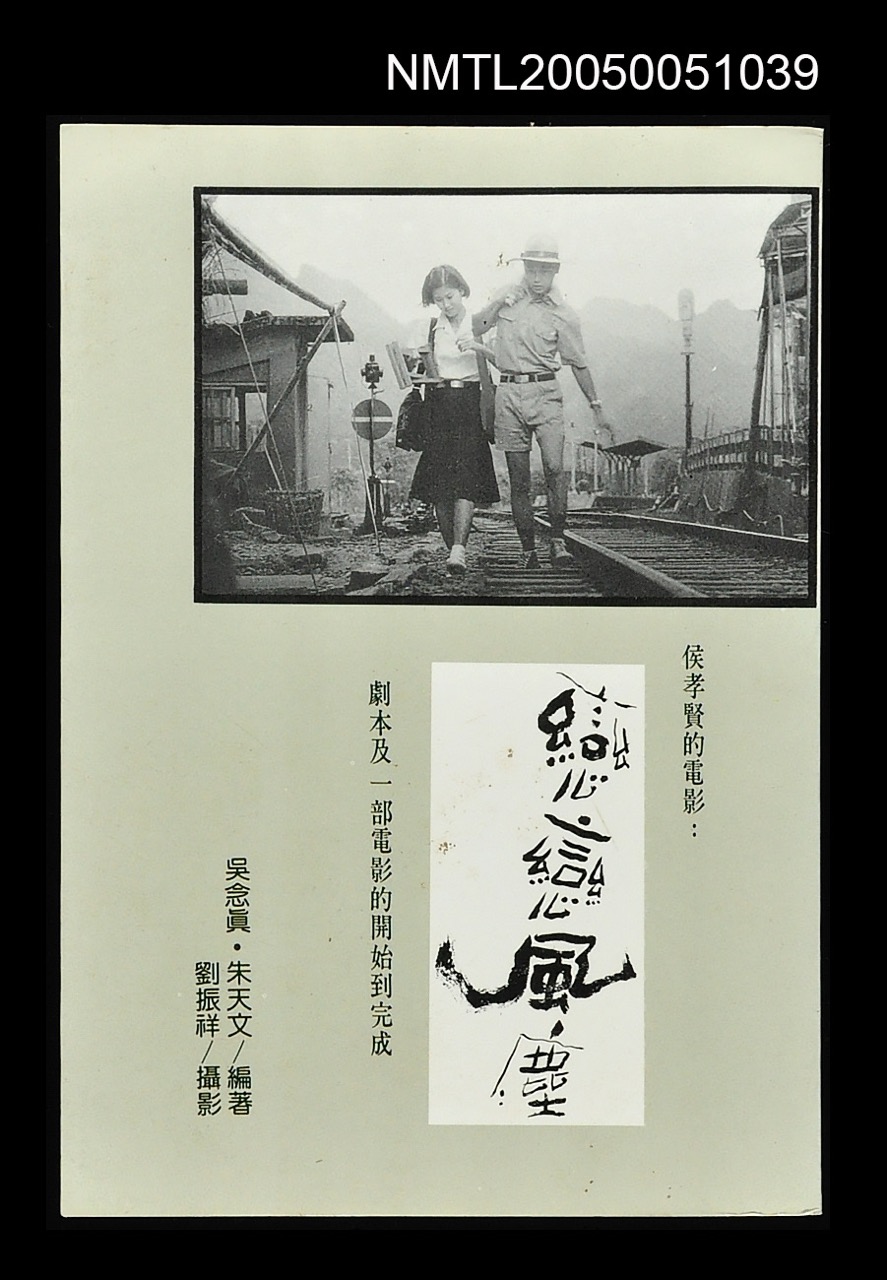

Wu Nien-chen and Chu Tien-wen Dust in the Wind, 1987 / Collection of The National Museum of Taiwan Literature

Directed by Hou Hsiao-hsien, Dust in the Wind (1986) portrays young people leaving their hometowns to seek work in cities during Taiwan’s 1970s urbanization. The film is based on Wu Nien-chen’s personal experiences, with the screenplay co-written by Wu and Chu.

Chung Chao-cheng After The Dull Ice Flower (Manuscript, 1989) / Collection of The National Museum of Taiwan Literature

The Dull Ice Flower, written thirty years earlier, addressed social issues such as election bribery and wealth disparity, which remain unresolved and have become more severe over time. Chung Chao-cheng believed that rescuing the increasingly deteriorating moral culture in Taiwan required collective effort.

Huang Chun-ming His Son's Big Doll, 1969 / Collection of The National Museum of Taiwan Literature

The story follows Kun-shu, who paints his face like a clown to survive, enduring ridicule and stares from villagers.

To ensure his young son can recognize him, he repeatedly paints his face, vividly portraying paternal love.

In 1983, the book was adapted by Wu Nien-chen into a three-part film directed by Hou Hsiao-hsien,

Tseng Chuang-hsiang, and Wan Jen: His Son's Big Doll, Vicki’s Hat, and The Taste of Apples.

The trilogy was released under the title The Sandwich Man by Central Motion Picture Corporation and brought to the screen,

generating generating heated political debate.

This adaptation not only marked the beginning of Taiwanese New Cinema movement but also sparked a wave of novel-to-film adaptations.

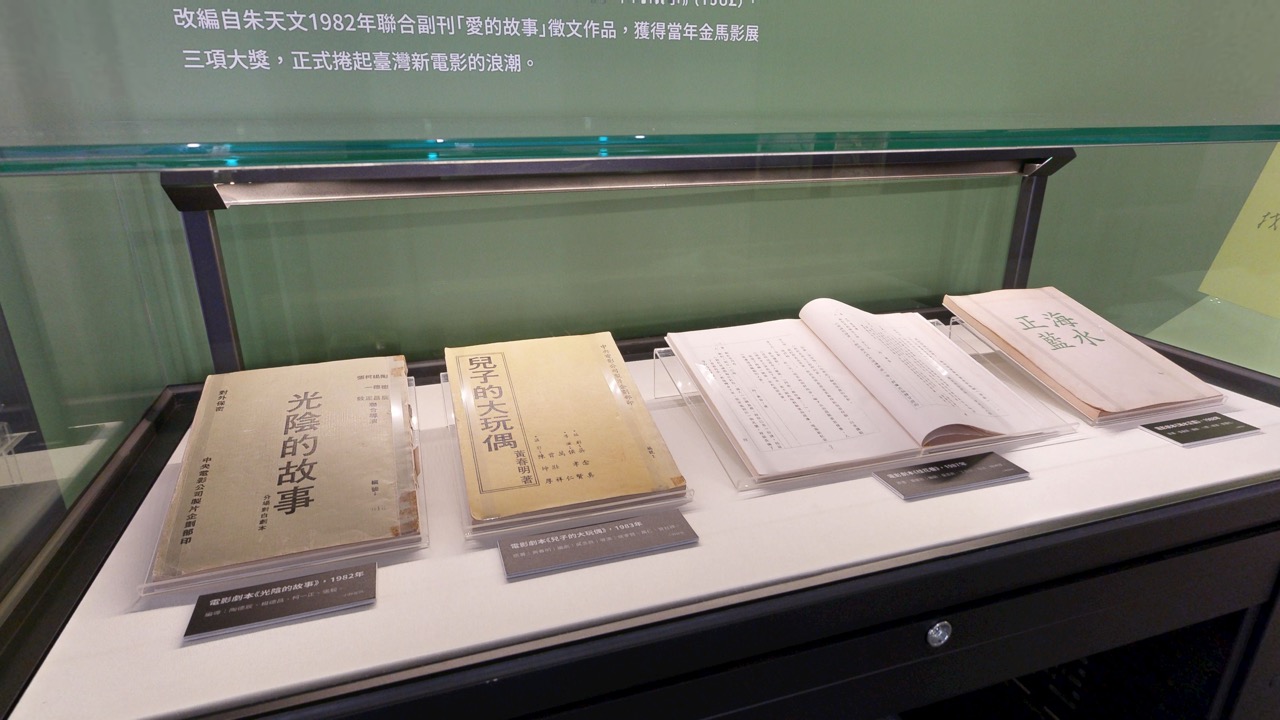

Film Script In Our Time, 1982、His Son's Big Doll, 1983、Osmanthus Alley, 1987、When the Ocean Is Blue, 1988 / Courtesy of Hsiaoyeh

Liberating Sex and Gender: Post-1980s Gender Literature and Film

Liberating Sex and Gender: Post-1980s Gender Literature and Film

The 1980s were a period of passion and civic energy. The party-state began to loosen its grip, yet the shadow of authoritarianism still hung heavy in the air, sparking social movements. New Cinema harnessed this rebellious sentiment, exploring desire and challenging conservative industry structures with suggestive visual storytelling, paving the way for the 1990s’ liberalization of sexuality and gender expression. In 1981, Sylvia Chang, inspired by Yuan Chiung-chiung’s A Place of One's Own, co-produced with Chen Chun-tien a television adaptation of Erya Publishing’s Eleven Women, published in 1981, voicing the inner journey of women in a new era striving for independence and the freedom to be themselves.

In post-1980s, films addressing gender issues diversified, including Watching the Sea, Rapeseed, The Butcher’s Wife, Kuei-Mei, a Woman, and Jade Love, respectively adapted from the works by Huang Chun-ming, Liao Hui-ying, Li Ang, Julia Hsiao, and Pai Hsien-yung.

In 1985, Jack Lin adapted Pai Hsien-yung’s novel "Love’s Lone Flower", published in 1970, into a film, which in its original form delicately portrayed deep emotional bonds between women, though the movie rendered these connections more subtly. In 1987, Chen Kun-hou directed Osmanthus Alley, adapted from Hsiao Li-hung’s novel of the same name, published in 1977, which also ambiguously touched on the budding affections between women. In 1986, Yu Kan-ping directed Crystal Boys, adapted from Pai Hsien-yung’s classic full-length gay novel, first serialized in 1977. When submitted for review, the film was initially banned by the Department of Information Services and was only allowed a restricted release after extensive cuts to scenes depicting male-male relationships. Chiang Lang’s The Silent Thrush, released in 1992, adapted from Ling Yen’s novel of the same name, published in 1990, is considered an early Taiwanese lesbian film, portraying love and desire between female performers in Taiwanese opera troupes.

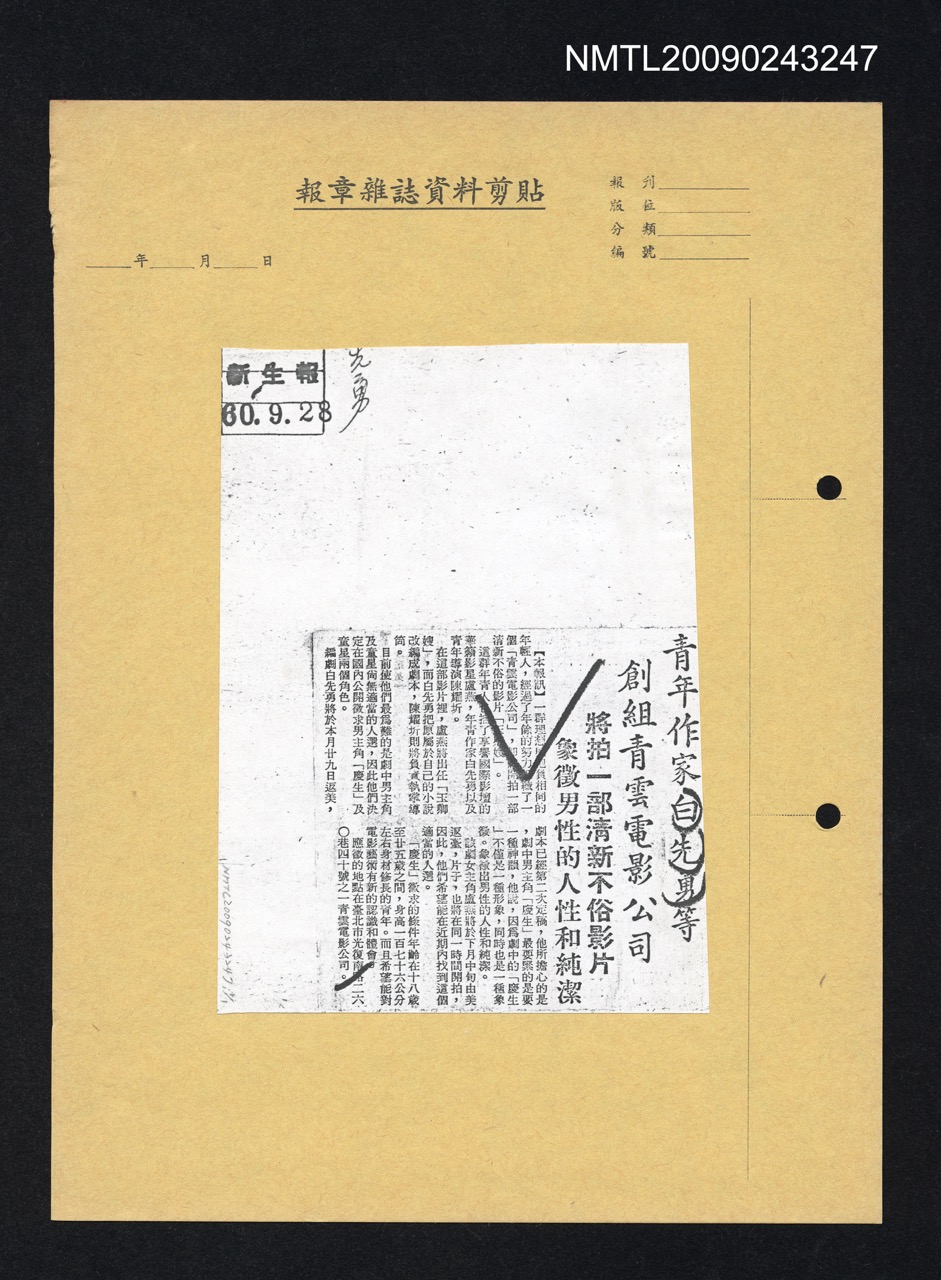

Young Writers Pai Hsien-yung and Others Founded Chingyun Film Company Clipping (Photocopy, 1971) Taiwan Shin Sheng Daily News

/ Collection of The National Museum of Taiwan Literature

[Trail of Equality and Art as Vanguard]

Unfolding the history of the twentieth century reveals a record of Taiwan’s struggle for equality, inscribed with the lives, blood, and tears of women and gender-diverse groups. Taiwanese women, freed from foot binding in the early 20th century, gradually gained access to education and employment while navigating tensions between arranged marriages and love without restraint. Postwar, they slowly moved beyond the tradition of “child brides” to find “a place of one’s own,” yet issues like domestic violence, human trafficking, and gender-based abuse persisted into the 1980s and 1990s, with slow institutional reform.

Literature, film, and other artistic works addressing gender have played a vital role in both resistance and reform - - The works displayed here each embody a story of blood and tears, symbolizing the towering walls of patriarchal power that the marginalized - such as the youths in Crystal Boys and women resisting oppression - struggled against. Each piece also stands as a landmark of gender equality, like a rainbow after the rain, guiding Taiwanese society toward the light during the season of blossoming.

Rapeseed-Related News (News Clipping 1984) China Times / Collection of The National Museum of Taiwan Literature