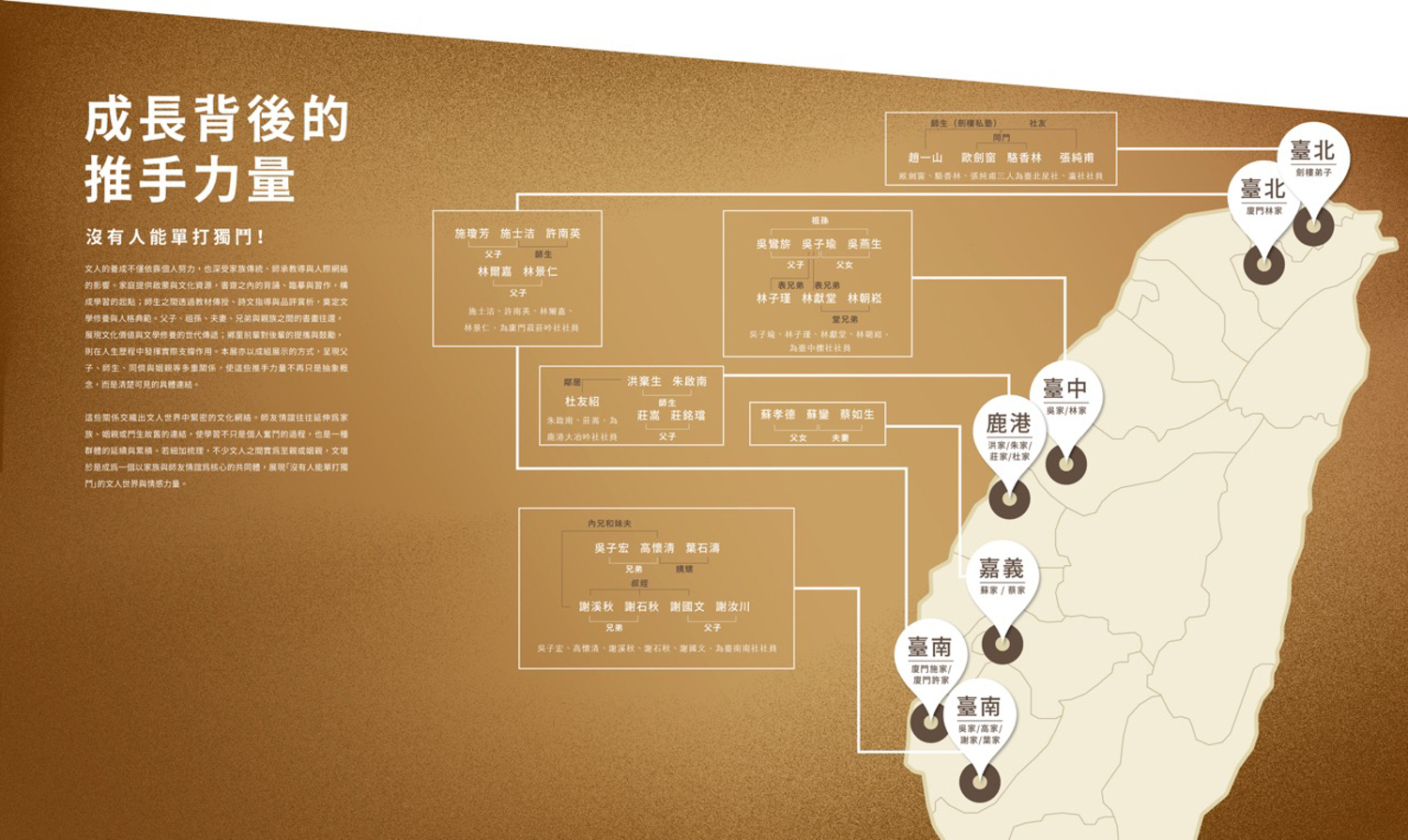

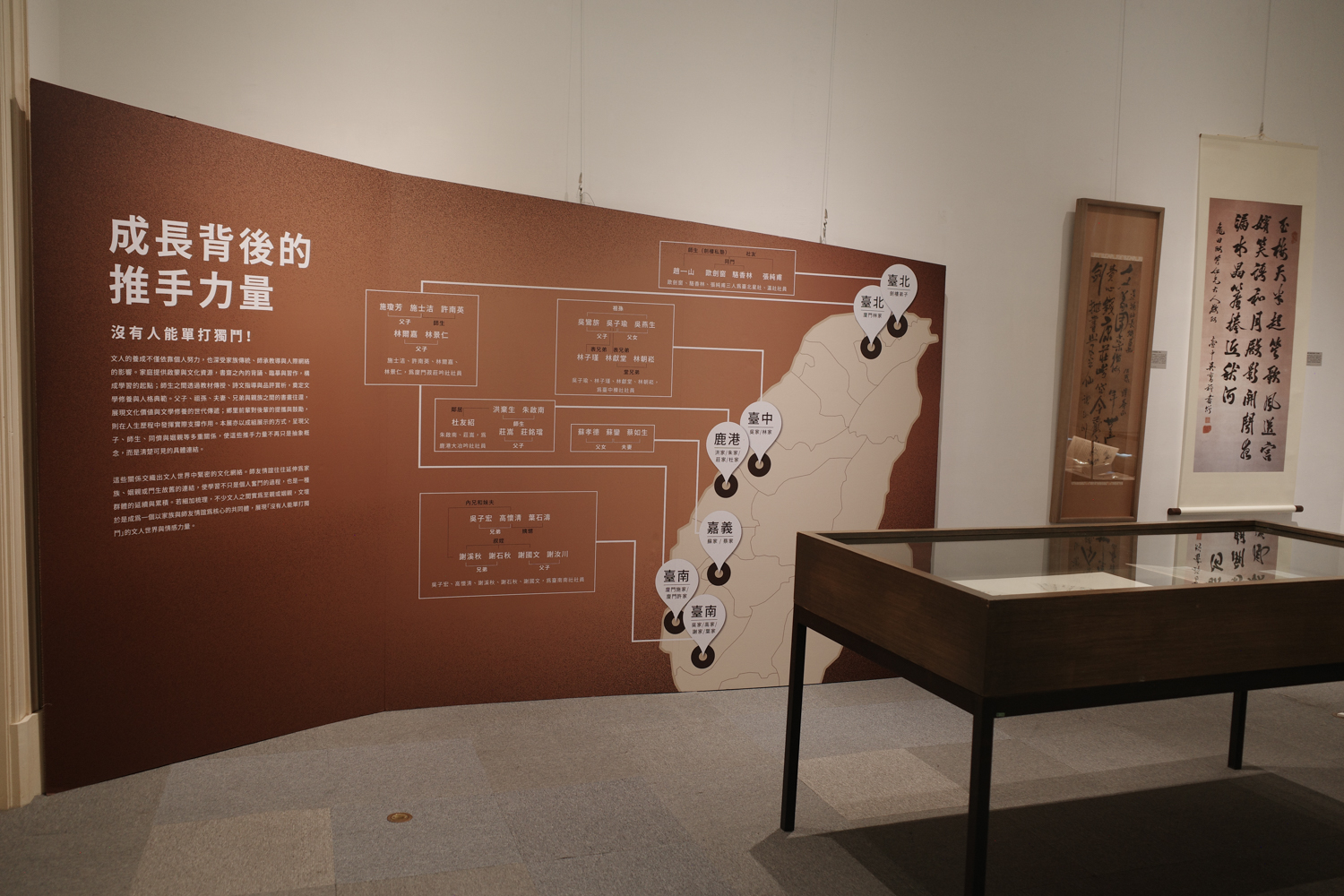

Helping Hands Along the Way

Nobody Fights Alone!

Nobody could become cultivate themselves into a scholar all on their own. The traditions of the household scholars came from, the advice and coaching of their teachers and mentors, and the social groups which they moved in all had an influence. A household provided childhood education and cultural grounding; reciting classics and imitating masters of calligraphy in the study formed the starting point of their education. Through lessons taught, poetry coached through, and feedback and analysis given, teachers established an attitude of self-cultivation and a sense of character in students. The painting and calligraphy exchanged between fathers and sons, grandparents and grandchildren, husbands and wives, and brothers and relatives passed cultural values and literary cultivation from one generation to another, with the guidance and encouragement given to young students by elders providing substantial practical support throughout their lives.

These relationships intertwined to form a close-knit cultural network among intellectuals. The bond between scholars often extended to family members, in-laws, students, and old friends. This meant that study was not only a personal struggle, but an extension and focal point of the whole community. Looking more closely, many intellectuals were actually closely related by bloodline or marriage. Literary circles thus became communities centered around family and mentorship, epitomizing the sentiment of the educated class that nobody could succeed on their own.

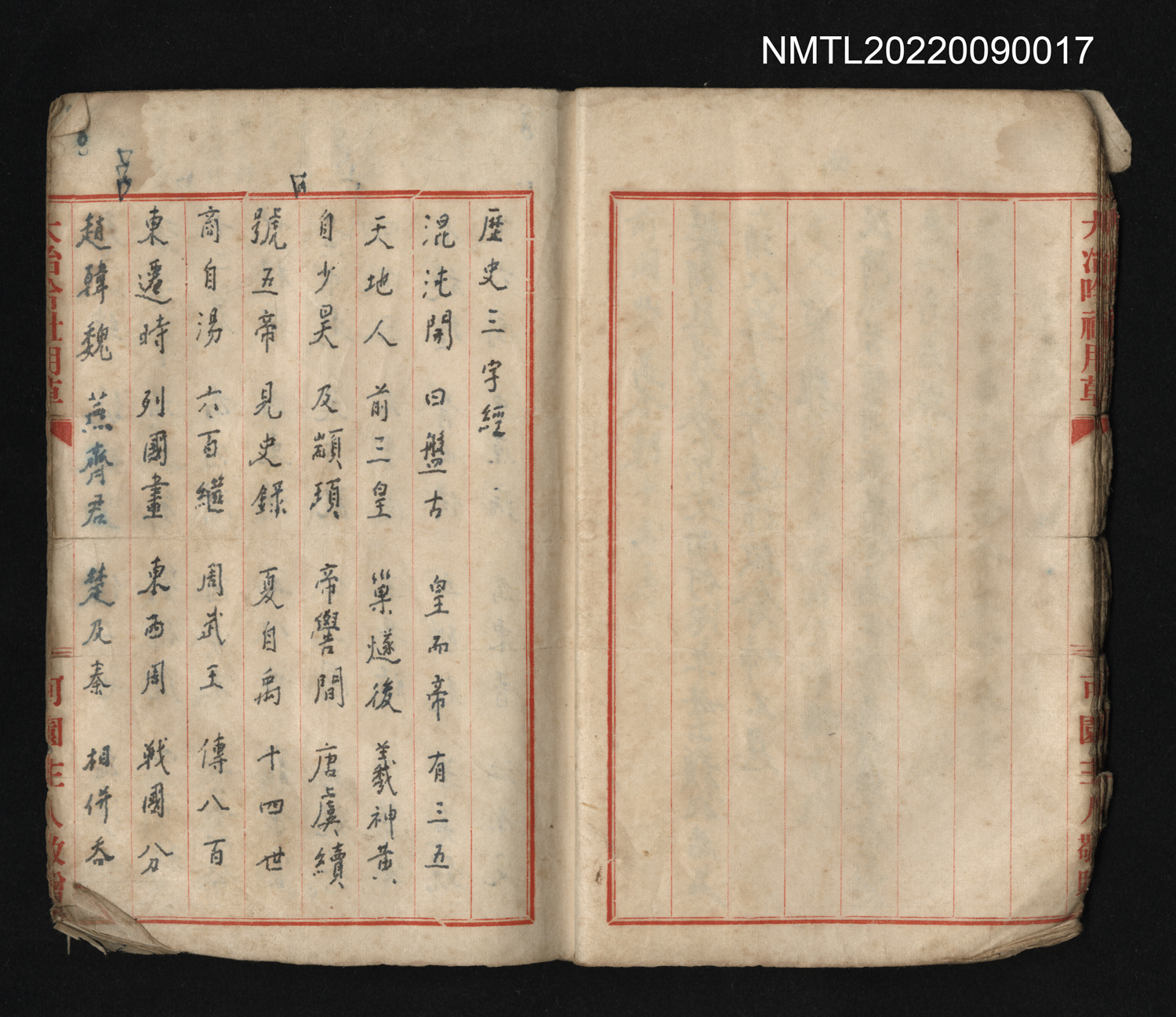

|"Three-character Classic of History," Chu Chi-nan, date unknown|

These are notes by Chu Chi-nan, open to his copy of the "Three-character Book of History." This book was the first half of the "Contemporary Three-character Reader" compiled by his teacher, Hung Chi-sheng (1866-1928), in 1897. Using three-character phrases and sentences to explain Chinese history and places, the "Contemporary Three-character Reader" functioned as an educational primer for children. It is divided into two parts: the "Three-character Book of History" and "Three-character Book of Geography." It is written on note paper from the Daye Poetry Society, which was established in Lukang, Changhua County in 1921.

NMTL20220090017 / Donated by the family of Chu Chi-nan

|Ji He Zhai Collection, volume 6, Hung Chi-sheng (1866-1928), 1910-20|

These are poems by Hung Chi-sheng (1866-1928), but their inscriber is unknown. The Ji He Zhai Collection includes poems, formal poetic pianwen prose, classical literature, and contemporary test poems, all named variations of Ji He Zhai. It is open to the seven-character poem "Growing Hair," which was written after Japanese police forced Hung Chi-sheng to shave his queue. It expresses his determination to resist cutting his hair and his resolve to uphold and protect traditional Han culture. The last line of the poem is: "How can a few strands of thinning hair remain strong and unyielding? In such times one must learn to live on the dregs." Here, the sparse queue symbolizes a will that refuses to go with the flow, reflecting both the cultural conflicts brought by colonial rule and his own will to persevere.

NMTL20060360003-006 / Donated by Hung Hsiao-ru

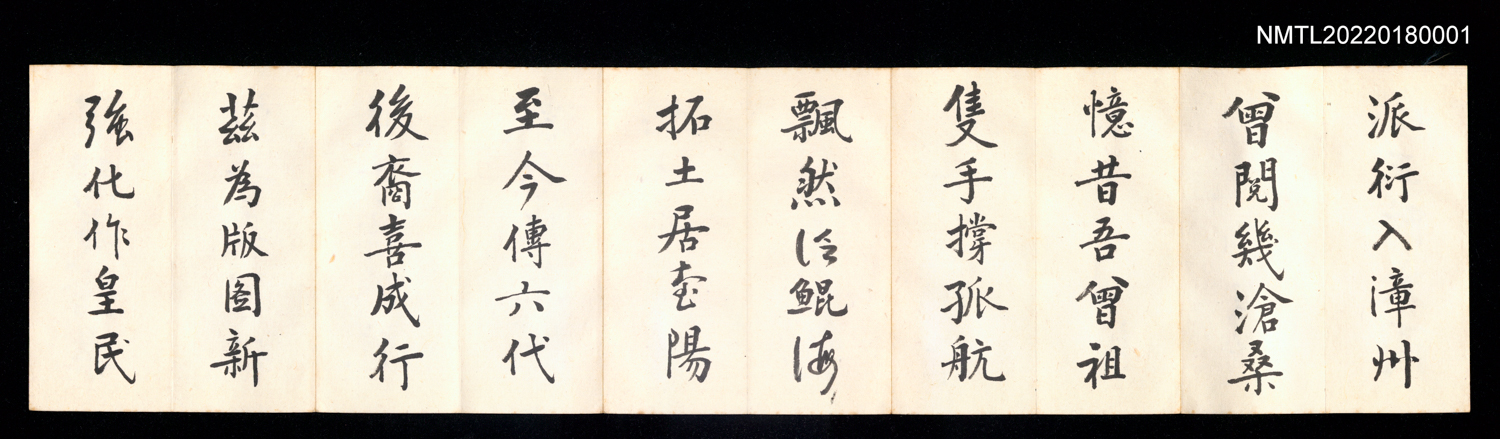

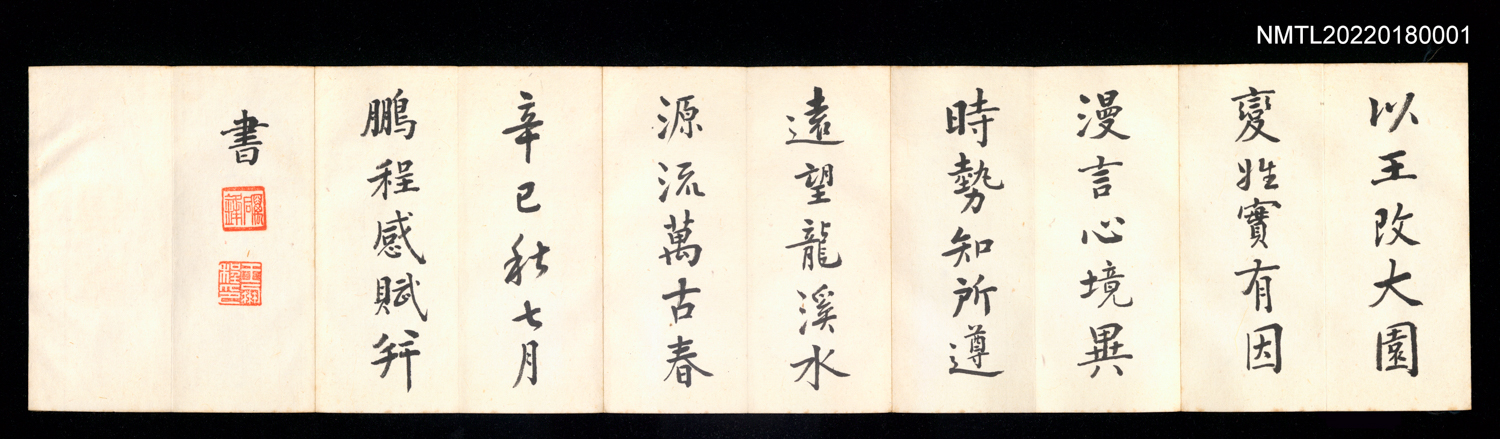

|"There Was Indeed Reason For This Change," Wang Peng-cheng, 1941|

These are Wang Peng-cheng's poem manuscripts in butterfly binding. "On Changing One's Name" is a classical five-character poem written in 1941, while the the Japanese colonial government was promoting its Japanization policy of name-changing. Wang Peng-cheng changed his name to Dayuan Peng-cheng. The poem alludes to the stories of Jiang Ziya and Fan Li (who both changed their names) as he reflects on his family's migration from the Minnan region to Taiwan. The line "From Wang to Dayuan; there was indeed reason for this change," expresses his mental state of changing his name in order to keep up with the times. The poem is written to memorialize his family's origins and history, and his complex sentiments towards contemporary changes.

NMTL20220180001 / Donated by the family of Wang Te-chung

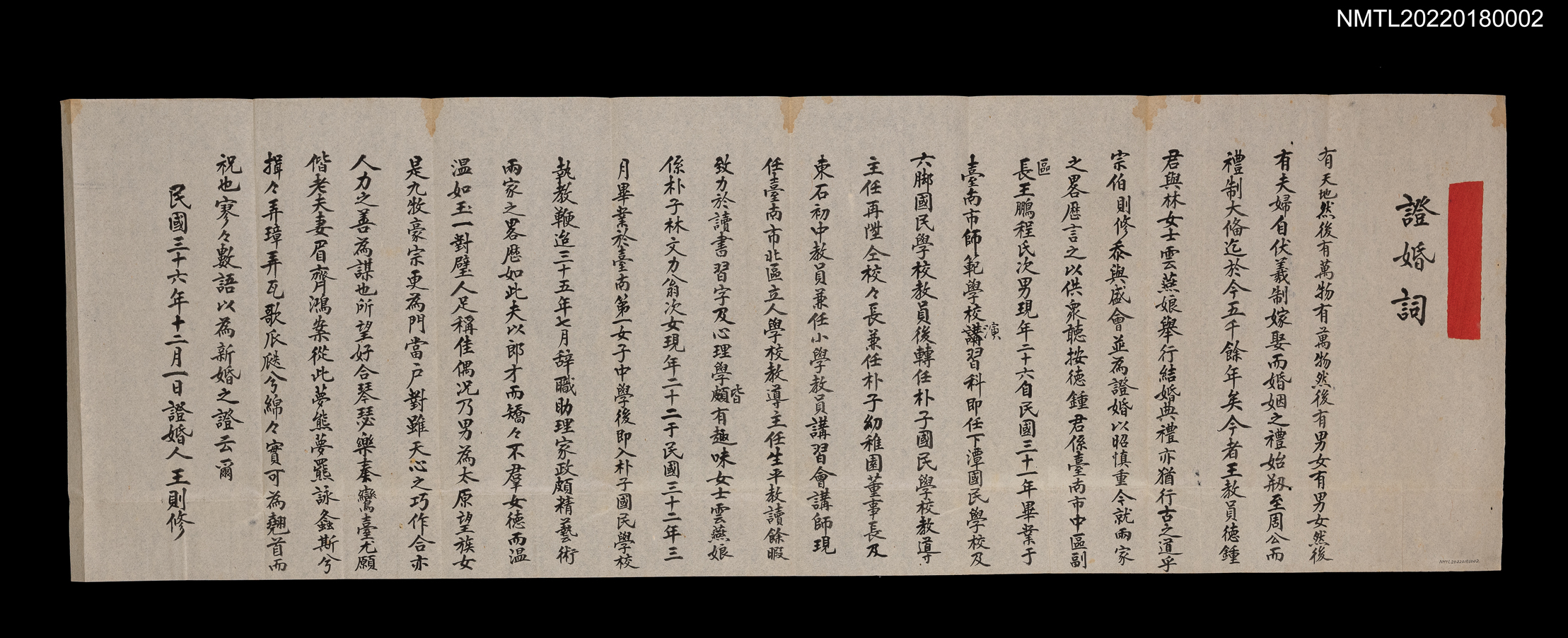

|Marriage Testimonial, Wang Tse-hsiu, 1947|

This is the handwritten marriage testimonial for the wedding of Wang Te-chung and Lin Yun-yan, written by Wang Tse-hsiu in regular script. Wang Te-chung was the second son of Wang Peng-cheng, who was a student of Wang Tse-hsiu. The text praises the newlywed's aptitude in studies, and hopes that their marriage will be harmonious and fulfilling, supporting both personal virtue and professional excellence, and allowing them to contribute to society. It functions as not only proof of the wedding, but a statement of blessing by the older generation of scholars, and an expression of their passing the torch of their families and knowledge to the next generation.

NMTL20220180002 / Donated by the family of Wang Te-chung

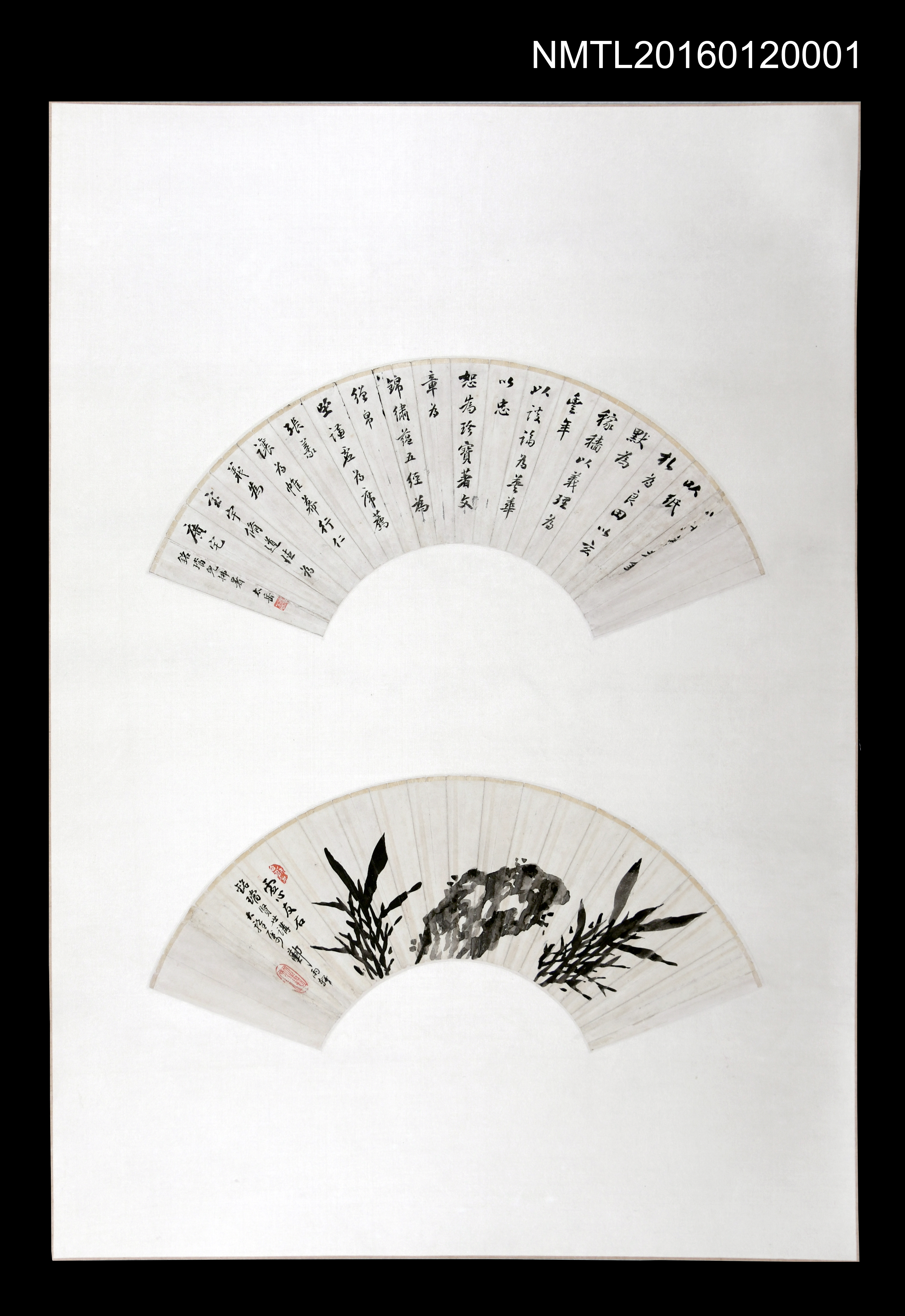

|Painted Fan, Chuang Sung and Cheng Yu-hsuan, 1930s|

This fan was a gift given by Chuang Sung to his second son, Chuang Ming-dang. On one side of the fan, bamboo and rocks are painted, accompanied by the inscription "Befriending rocks with an open heart; dedicated to the virtuous and refined Master [Chuang] Ming Dang" by Cheng Yu-hsuan. On the other side, Chuang Sung inscribed in semi-cursive script an excerpt from the "Appreciation and Praise" chapter of A New Account of the Tales of the World, extolling the self-cultivation of literati.

Bamboo and rocks symbolize faithfulness and willingness to learn, while the excerpt from "Appreciation and Praise" carries the ideals of literary and moral cultivation. Hence, this fan expresses both the father's earnest hopes for his son, and the cultural inheritance passed on from teacher to student.

NMTL20160120001 / Donated by Chuang Yung-sui

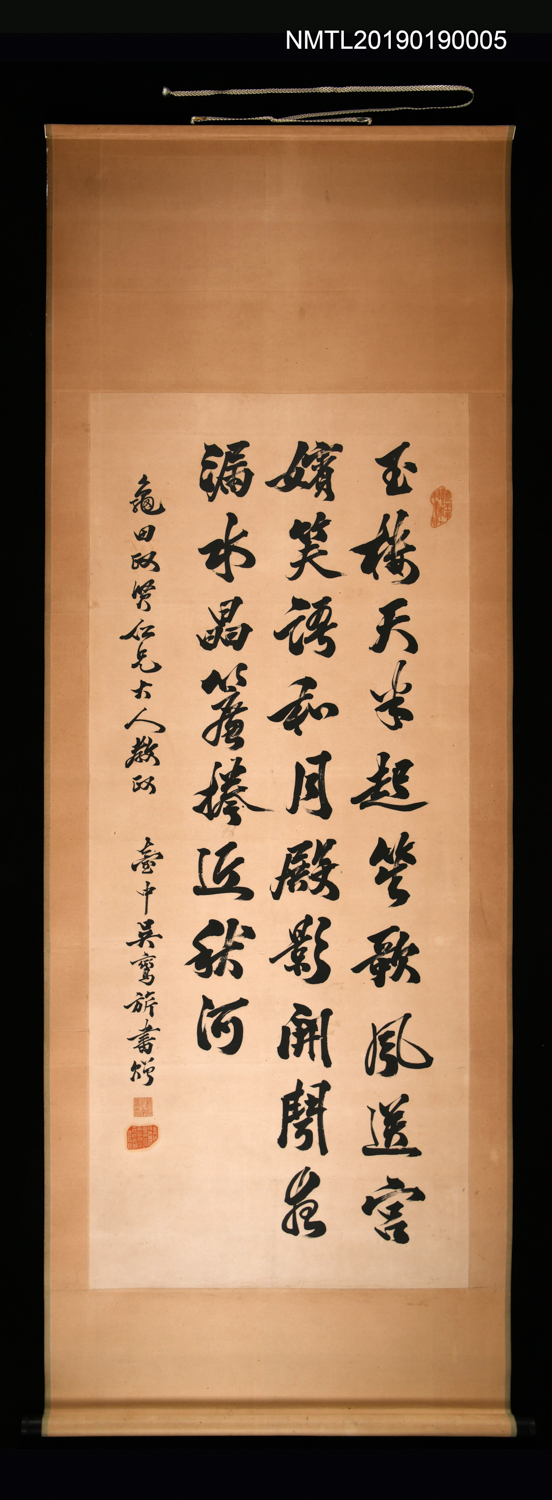

|Wall Scroll of Poem by Gu Kuang, inscribed by Wu Luan-chi in semi-cursive script, Japanese colonial era|

This is a transcription of Tang dynasty poet Gu Kuang's "Palace Verse." It reads:

"From the jade towers reaching to the heavens rise the sounds of pipes and song;

on the breeze is the laughter of palace women.

The shadows cast by the moon shift, and I hear the beat of the night watchman's drum;

as the crystal curtain rolls away, I seem to draw near the Milky Way."

The inscription reads "Respectfully presented to my dear Kameda Masahiro for his instruction."

Wu Luan-chi was a member of the Taichung gentry during the Japanese colonial era, and the father of Oak Poetry Society member Wu Tzu-yü. He was a skilled writer and calligrapher, but few of his works survive. This work is based on Yan Zhengqing's regular script; its powerful brushstrokes and open, flowing structure demonstrate deep calligraphic skill and refinement.

NMTL20190190005

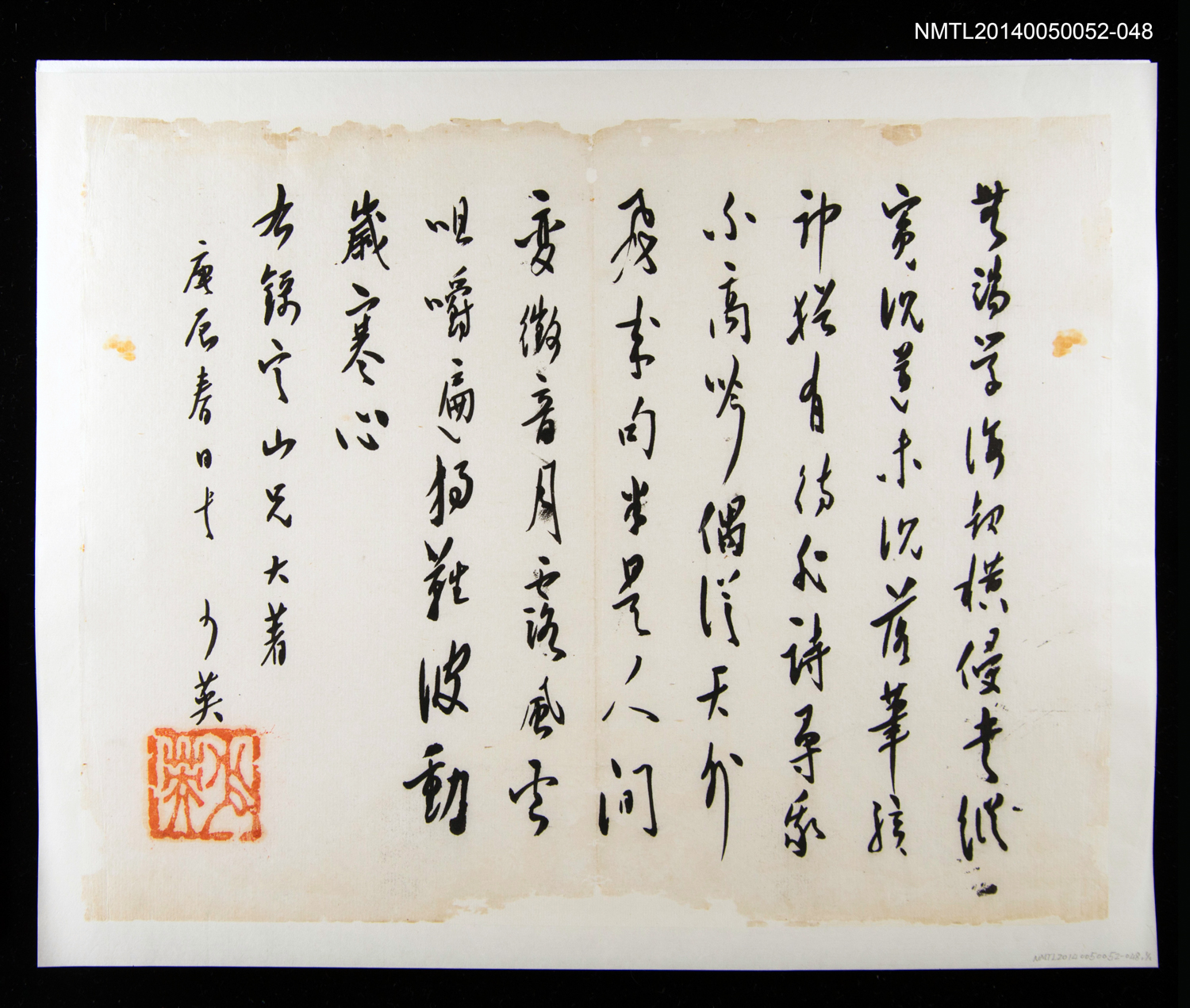

|Poem by Chou Ting-shan, inscribed by Lin Tsu-chin, 1940|

This is Chou Ting-shan's seven-character poem "Unexpected."

"Unexpectedly, the sea of knowledge has been invaded by calamity;

writings are buried in injustice, but my will is not.

My pen strokes can move the gods, but still need refinement;

if the poetry is not mine, I cannot sing it aloud.

Sometimes a line seems to fly in from beyond the heavens,

yet half of it carries the pain of the human world.

I have thoroughly appreciated the moon, dew, wind, and clouds;

yet they cannot stir the heart that endures the frost."

Lin Tsu-chin (courtesy name Shaoying) was Wu Tzu-yü's cousin, and a member of the Oak Poetry Society. This rendition of a friend's poem in semi-cursive script shows the friendship between scholars, and how they would exchange and answer each other's poems.

NMTL20140050052-048 / Donated by the family of Chou Ting-shan

|Letter from Lin Hsien-tang to Liang Qichao, 1912|

This is the draft copy of a letter from Lin Hsien-tang to Chinese thinker Liang Qichao. The letter discusses the collapse of the Qing dynasty: "The Tibetans were the first to rise up. The Mongols and Manchus will surely do the same." This shows the close attention intellectuals in Japanese-ruled Taiwan were paying to international relations and the breakup of the Qing Empire, while considering what it meant for the future of nationalist movements in Taiwan.

Liang Qichao was invited to Taiwan in 1911, where he met Lin Hsien-tang, Lin Yu-chun, Lin Chao-song, and other members of the Oak Poetry Society. Poetry and literary societies were closely intertwined with familial relationships, reflecting how intellectual and interpersonal relationships overlapped within Taiwan's literary circles.

NMTL20100020222 / Donated by Huang Te-shih

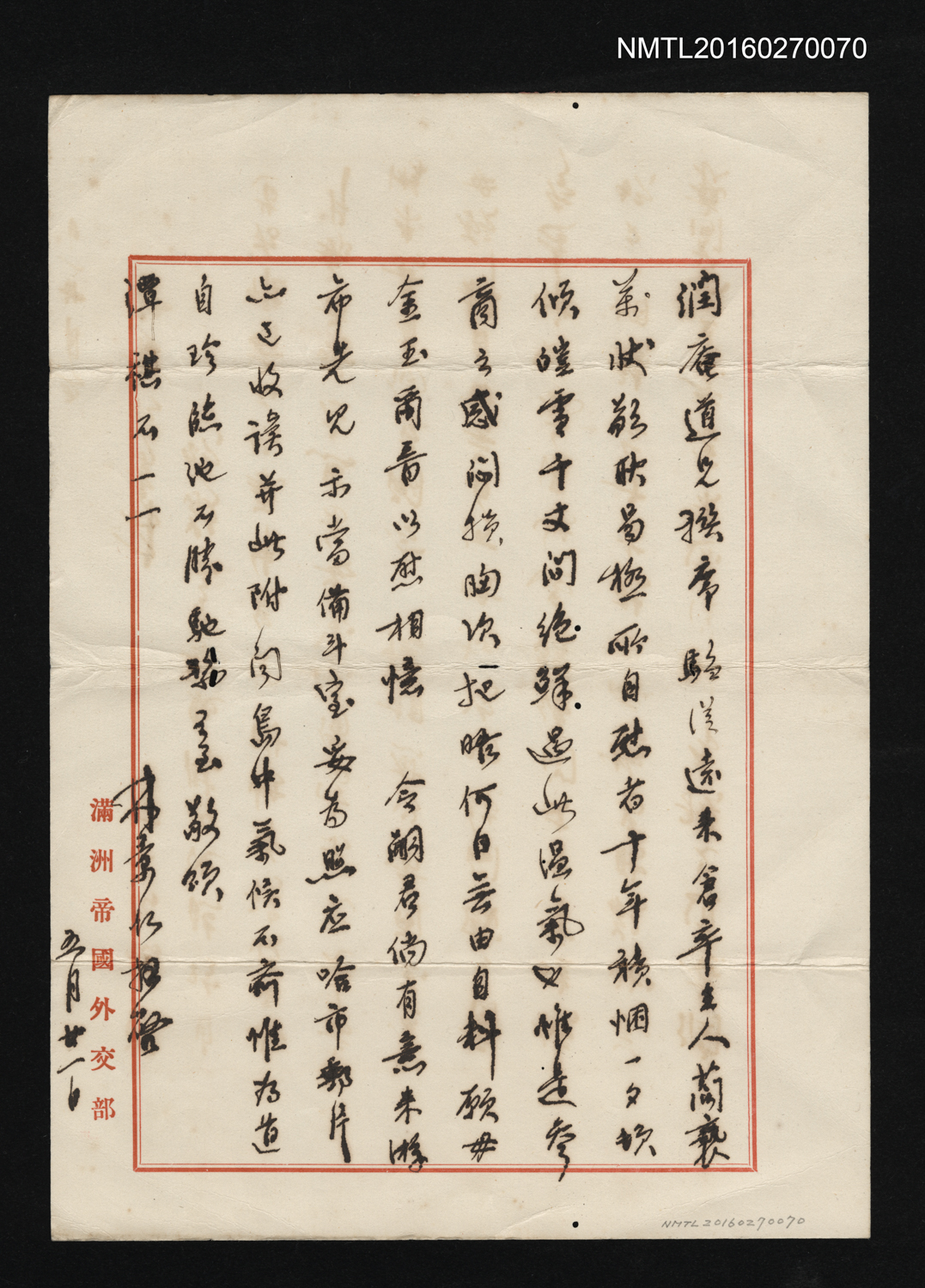

|Letter from Lin Ching-jen to Wei Ch'ing-tê, 1936|

This cordial letter from Lin Ching-jen in Manchuria to Wei Ch'ing-tê (pen name Jun An) in Taiwan includes, "If your son intends to visit, please notify me beforehand, and I will prepare a small room to accommodate him..." The letter was written while he was working at the Manchukuo Ministry of Foreign Affairs, reflecting the exchanges between Taiwan's intellectuals and northeast China during its occupation, and the care which they showed for one another.

NMTL20160270070 / Donated by Wei Ju-lin

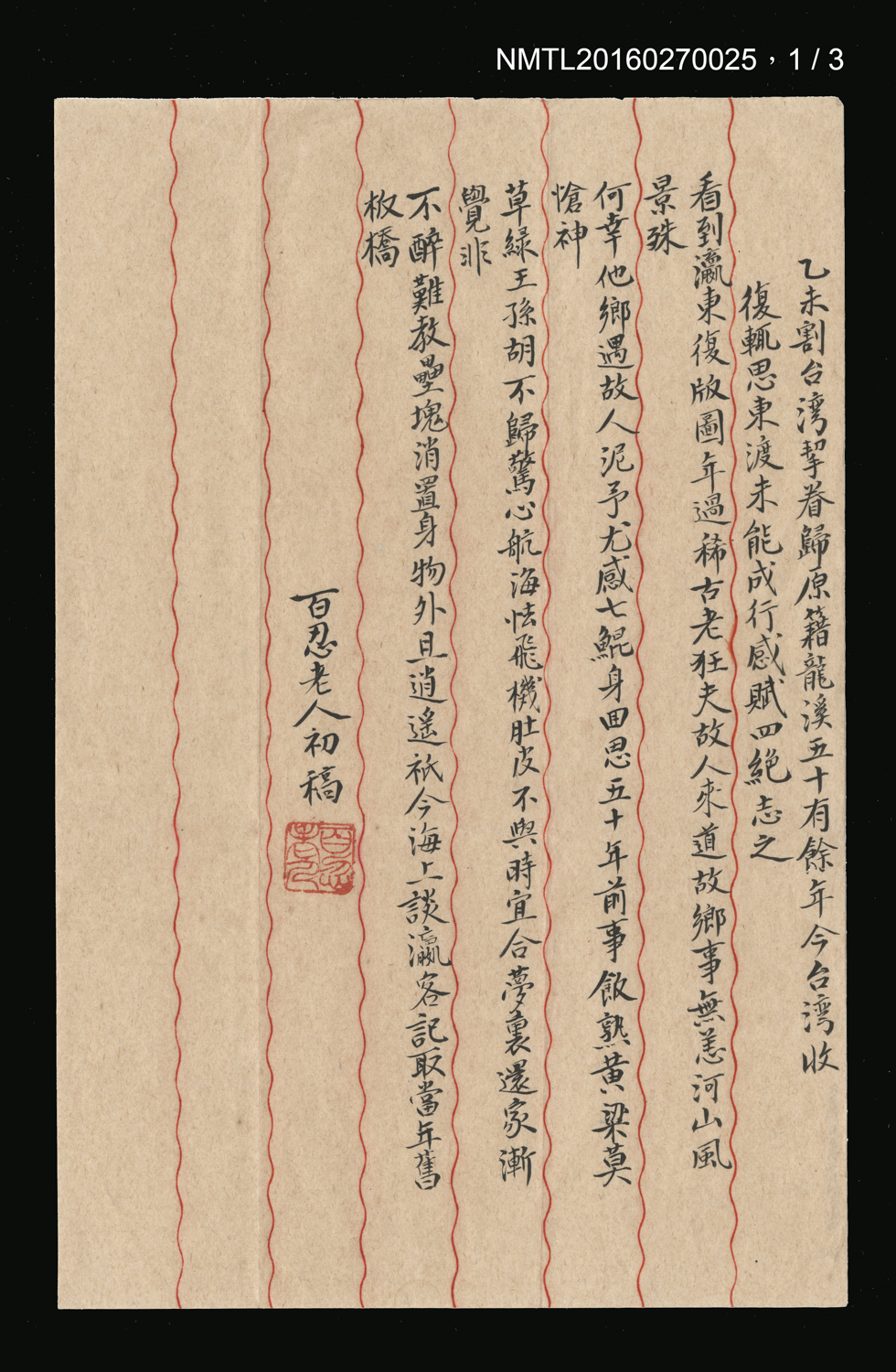

|Four Rhapsodies on Feelings Around the Recovery of Taiwan. Lim Nee Kar, 1945.|

In these four seven-character poems, Lim Nee Kar (pen name Bairen Laoren) expresses the emotional impact of Taiwan's retrocession in 1945. He reflects back on his family's flight to Longxi after Taiwan became a Japanese colony in 1895, giving voice to fifty years of homesickness in a foreign land, and the complex feelings stirred by his return to Taiwan. The manuscript was enclosed in a letter to Wei Ch'ing-tê, with "Humbly Presenting My Recent Works" written on the envelope, illustrating the scholarly tradition of expressing one's deepest aspirations and emotions through verse. Lim Nee Kar was the son of Lin Wei-yuan (of the Lins of Banqiao), and the father of Lin Ching-ren.

NMTL20160270025 / Donated by Wei Ju-lin

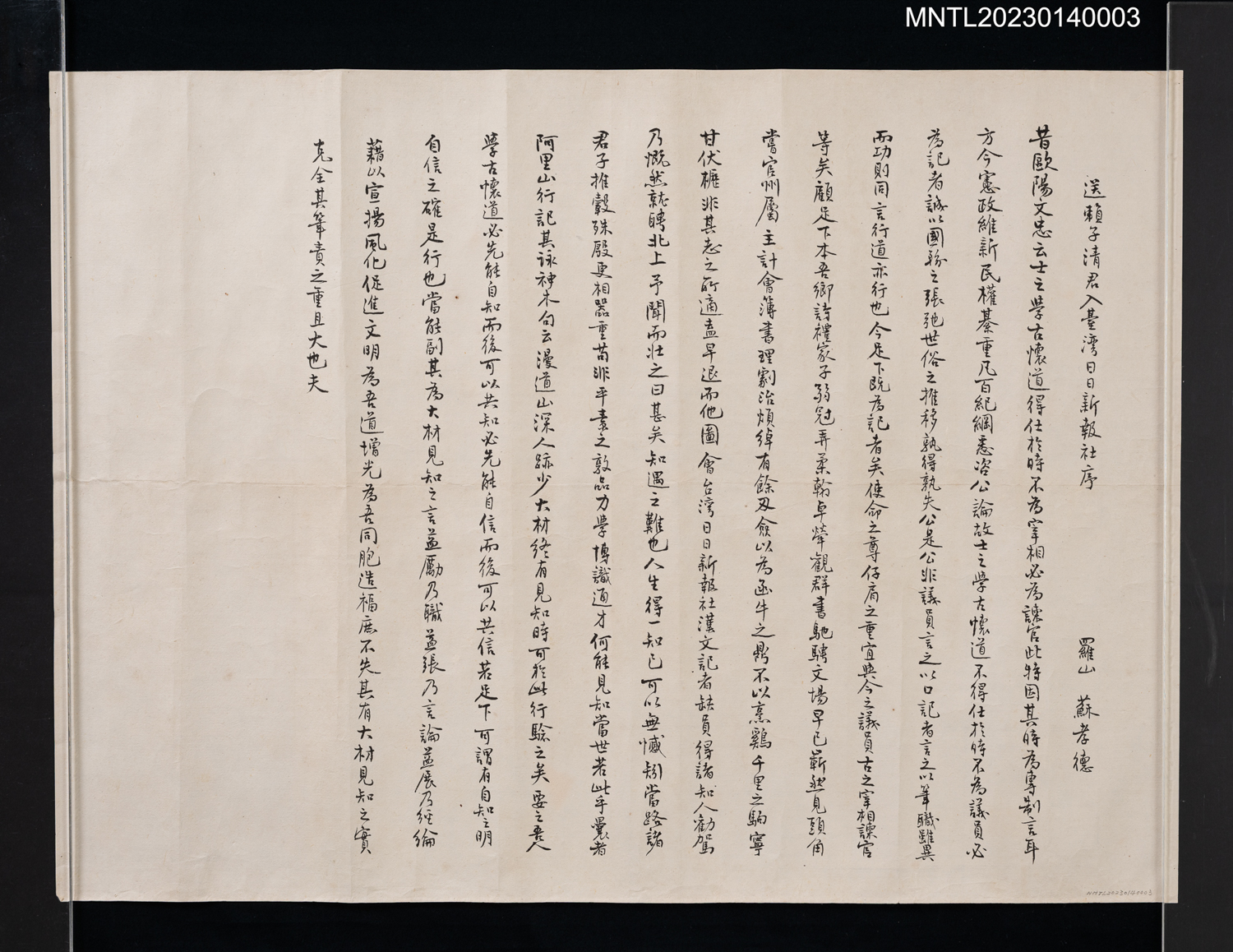

|Send-off for Lai Tzŭ-ch'ing to the Taiwan Daily News, Su Xiao-de, 1928|

Scholar Su Xiao-de and Lai Tzŭ-ch'ing shared the same hometown of Chiayi. Lai Tzŭ-ch'ing's' elders wrote these words of encouragement as a farewell upon his leaving for the Taiwan Daily News to take up his post as reporter. It reads, "Now that your path is that of a journalist, your mission is a respected one and your responsibilities heavy, just as today's legislators or yesteryear's scholar-officials." It calls upon him to write with integrity and stay true to his duties. With its elegant characters and neat and tidy semi-cursive script, this manuscript reflects the high expectations the upper class of the time held for those working in the news industry.

NMTL20230140003 / Donated by the family of Lai Tzŭ-ch'ing

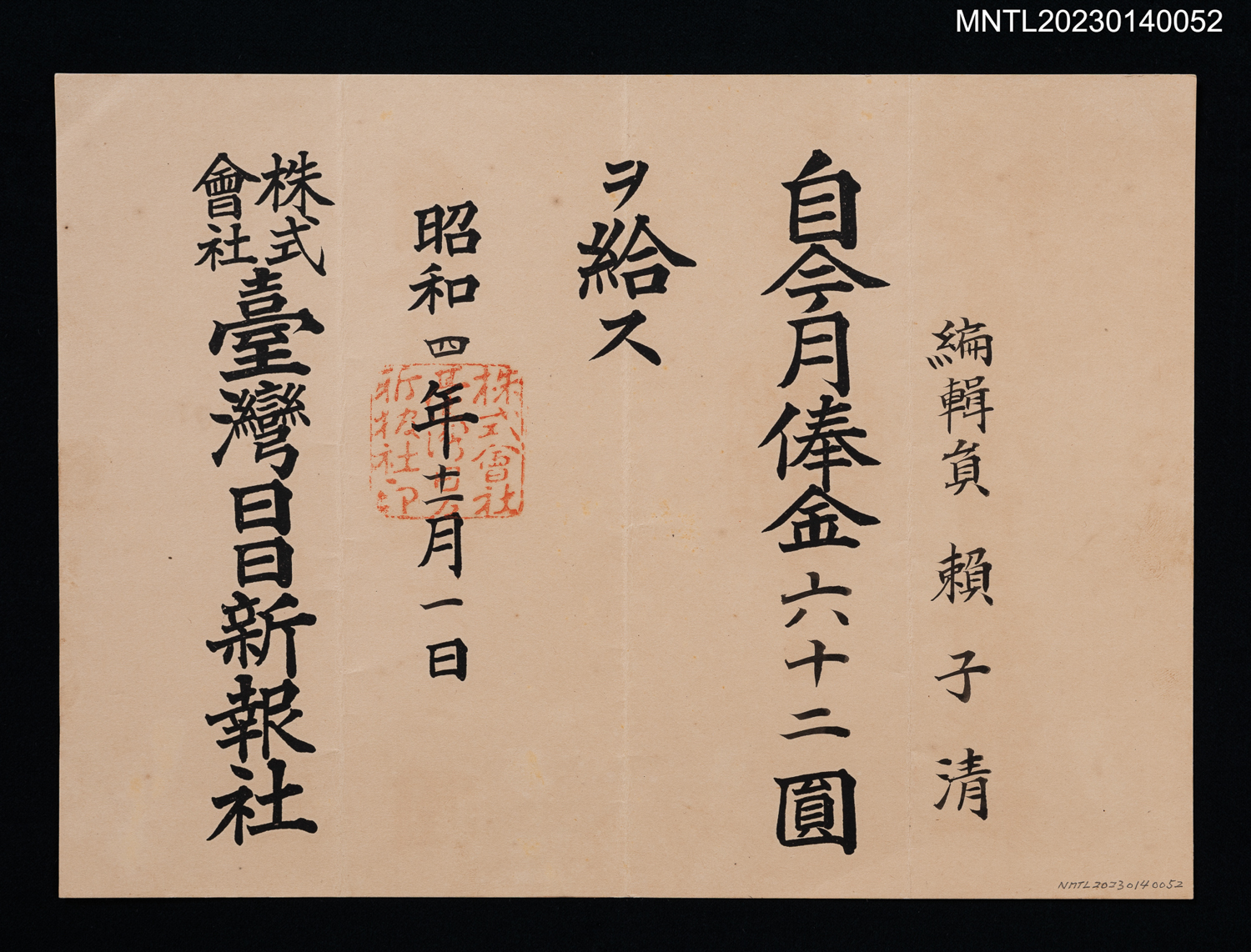

|Salary Statement for Lai Tzŭ-ch'ing, editor at the Taiwan Daily News, 1929|

This is a salary statement issued to Lai Tzŭ-ch'ing by Taiwan Daily News. It notes that effective that month, he became an editor, and would receive a monthly salary of 62 yuan. It is dated October 1, Shōwa 4 (1929). Statements like these served as proof of employment and the basis for remuneration. For us, they serve as references for understanding the income of educated literati working in the newspaper industry during the Japanese colonial era.

NMTL20230140052 / Donated by the family of Lai Tzŭ-ch'ing

|Su Luan's Transcription of Poem Prompts from a Timed Ji Bo Poetry Game, postwar|

This piece is a neatly written transcription of topics for a ji bo poetry gathering, copied by Su Luan in small, fine regular script. The topics are organized according to the thirty rhyme groups of the pingshui system, beginning with the dong rhyme, and are copied one by one in sequence.

Su Luan (pen name Ling Yun) was the eldest daughter of Chiayi poet Su Xiao-de, and the wife of poet Tsai Ru-sheng. She was active in Japanese colonial era and postwar poetry societies, and was skilled in both poetry and calligraphy. This document illustrates the participation of female poets in poetry society activities, and reflects the strict attention paid in ji bo gatherings to poem prompts and rhyming schemes.

NMTL20230370005 / Donated by Tang Bai-keng

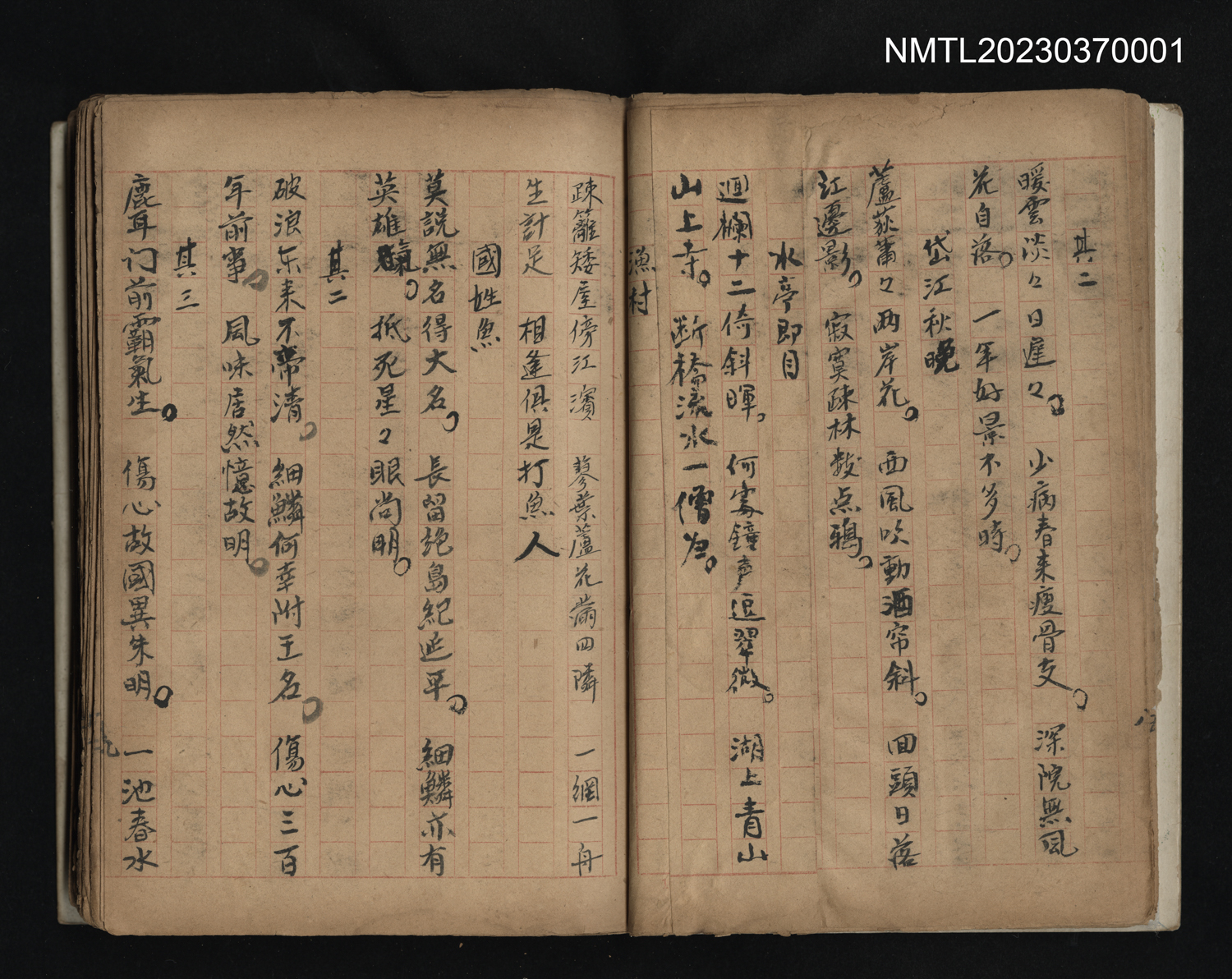

|Tsai Ru-sheng's Poetry Manuscript, Postwar|

This manuscript contains poems by Chiayi poet Tsai Ru-sheng, including the seven-character quatrain "The Guoxing Fish," the work which made him famous. In Shōwa 2 (1927), he submitted it to a poetry contest held by the Daijiang Poetry Society. Master critic Lien Heng granted it the rank of yuan (best) in this contest, bringing Tsai instant fame. The poem uses the milkfish as a metaphor for the deeds of Koxinga:

"Do not say the nameless can win no fame;

on this far-off island he left the tale of Yanping.

Even small scales can hold a hero's spirit;

till death, those bright, starry eyes still gleam."

In a turn of events which captured the imagination of the poetry world, this poem became widely celebrated, and earned Tsai Ru-sheng praise from Chiayi poet Su Xiao-de, whose eldest daughter, Su Luan, he later married.

NMTL20230370001 / Donated by Tang Bai-keng