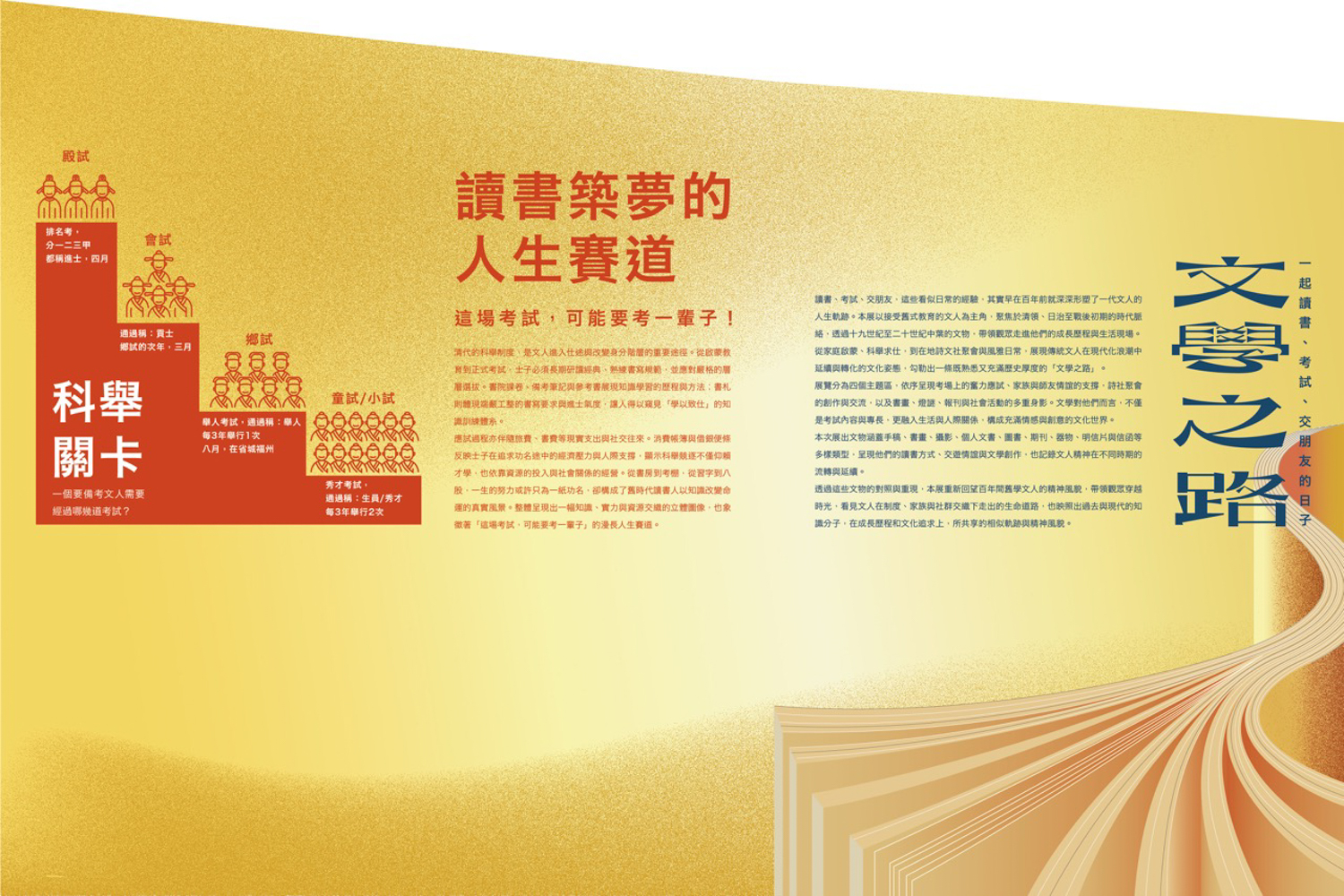

Building a Dream Through Study

An Exam That Lasts a Lifetime

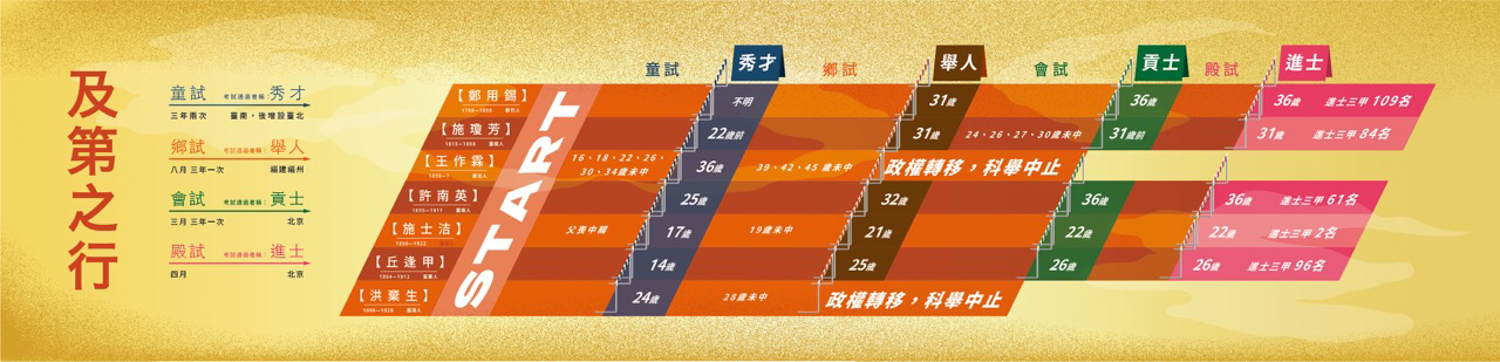

During the Qing dynasty, the imperial examinations were an important way of building an official career and changing one's social class. From their earliest education to the official examination, scholars were studying the Four Books and refining their writing, working to pass through a strict, multi-tiered selection process. Academy test papers, student notes, and reference books show us students' curricula and study methods; the letters they wrote attest to the stringent demands placed on their writing abilities, and give us a glimpse into the system of academic training that turned students into scholar officials.

With attempting that training came also traveling expenses, textbooks fees, and other practical monetary considerations, not to mention the social connections that had to be made. Account books and debt stubs reflect the financial stress which scholars bore and the interpersonal support they received in their pursuit of success, and attest to the fact that passing the imperial examinations relied on not just talent and scholarship, but also an individual's social and economic resources. Their entire lifetime of effort, from the study room to the examination booth, from learning Chinese characters to composing eight-legged essays, might be spent to acquire a single piece of paper granting them a title. Yet this was the everyday reality of how scholars of the time changed their lives through education. Put together, the overall image is a three-dimensional tableau of knowledge, practical abilities, and economics intertwined, affirming that for scholars, the exam might last a lifetime.

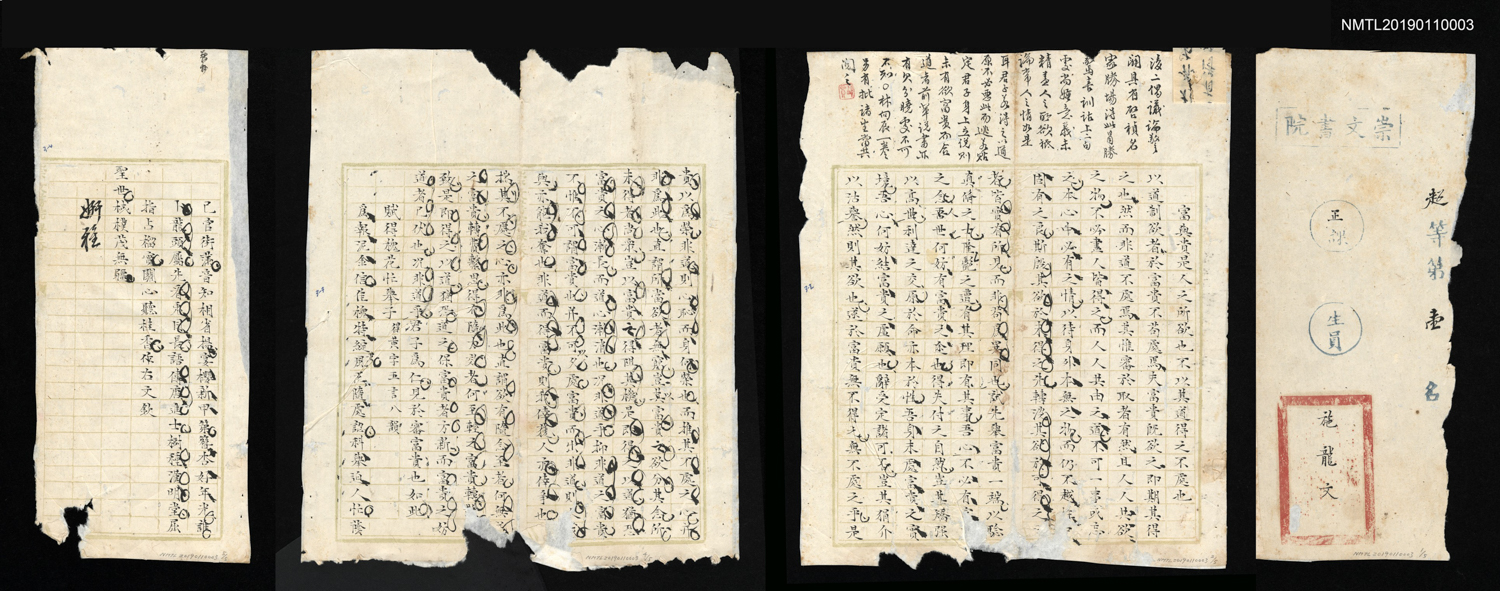

|Test Paper from Chongwen Academy, Shih Lung-wen, c.a. Daoguang 37 (1837)|

This test paper written by Shih Lung-wen at the Chongwen Academy received a grade of "superior" and was ranked first-place. The theme is from the chapter "Living in Brotherliness" of the Analects of Confucius: "Wealth and title are what all men desire, but they will not accept them unless they are acquired by the proper means." The Chongwen Academy was a Qing-era school for scholars to research, study, and prepare for the examinations. Every month, the Academy would hold one guan ke, a test administered by a local official, and one shi ke, a test led by the school's headmaster. Grades were determined by performance on the test's essay question and poem composition prompt.

Just like the eight-legged essay, the test poem was a part of the Qing dynasty's entry-, provincial-, and metropolitan-level exams. This is a practice test, written before he passed the entry-level exam. Shih Lung-wen, from Tainan, became a jinshi (advanced palace-level scholar) in 1845. He and his second son, Shih Shih-chi, became Taiwan's only father-and-son pair of jinshi.

NMTL20190110003 / Donated by the family of Yang Wen-fu.

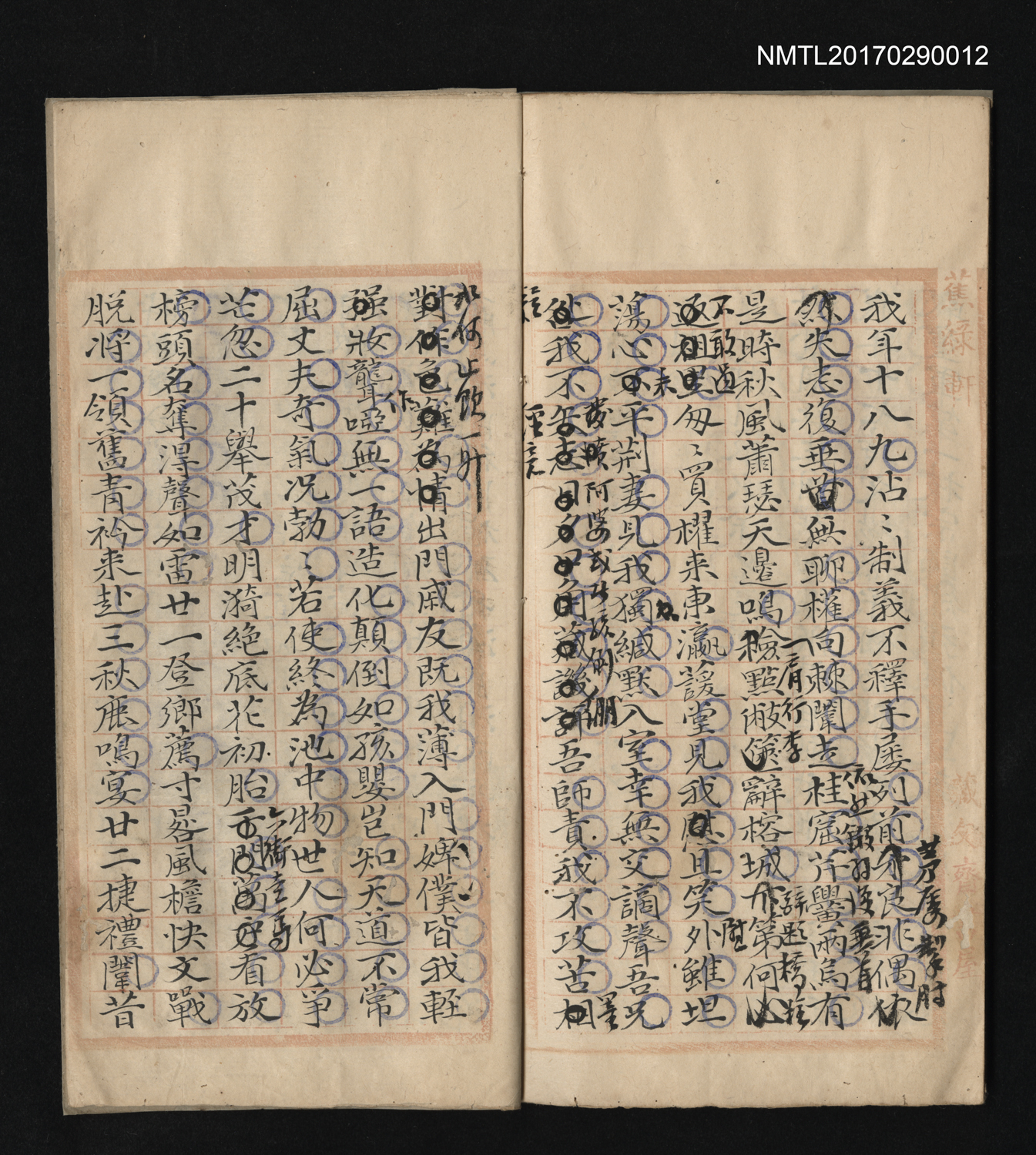

|Poems by Zhe Yuan, Shih Shih-chi, c.a. Guangxu 3 (1877)|

This is a collection of early poems by Shih Shih-chi (1856-1922, courtesy name Zhe Yuan), composed between 1870 and 1891, totaling six volumes, of which four survive. He composed one of them, "Reflections On New Year's Eve," upon achieving the rank of jinshi in 1876. His disdain for worldly fame and fortune come through in the line "If one is destined to remain limited and confined, why should he torment himself competing for petty glory?" This manuscript was completed before A Collection of Shrines After Su was compiled, thus providing us with an earlier version of his poems. Shih Shih-chi was a jinshi from Tainan who left Taiwan after 1895. His work reflects the experience and mood of contemporary scholars.

NMTL20170290012 / Donated by the family of Huang Tien-Ch'üan

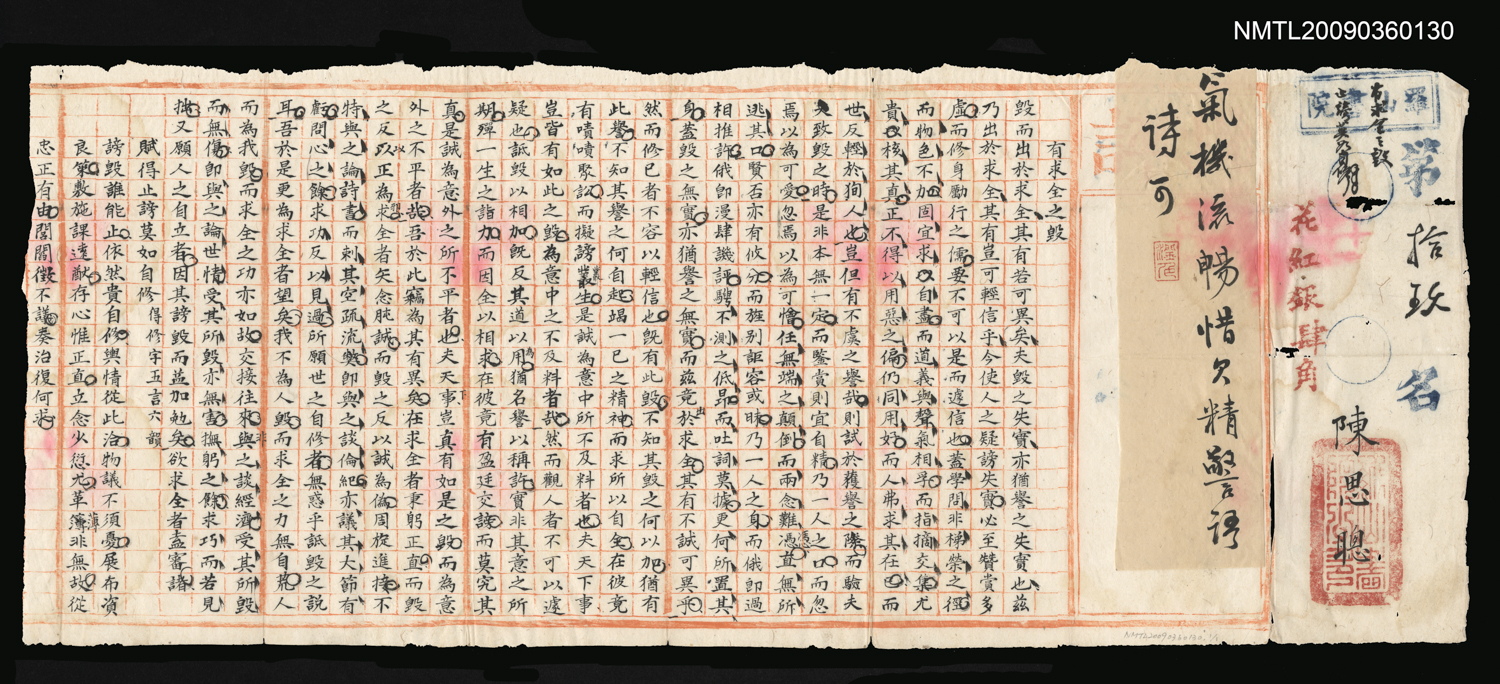

|Test Paper from Luoshan Academy, Chen Si-cong, early Guangxu era (1875-1908)|

A test paper from the Luoshan Academy in Chiayi. The essay prompt is "There are those who receive slander for pursuing perfection," which is a quote from the "Li Lao" chapter of Mencius. Testers at the Academy could earn prizes based on their grades and assessments. Chen Si-cong ranked 19th on this test, and was awarded a prize of four jiao of silver. The examiner's remarks are: "The essay reads smoothly, but lacks originality and memorable phrases. The poem is acceptable."

NMTL20090360130 / Donated by Chairman Chen Chung-kuang, Chen Cheng-po Cultural Foundation

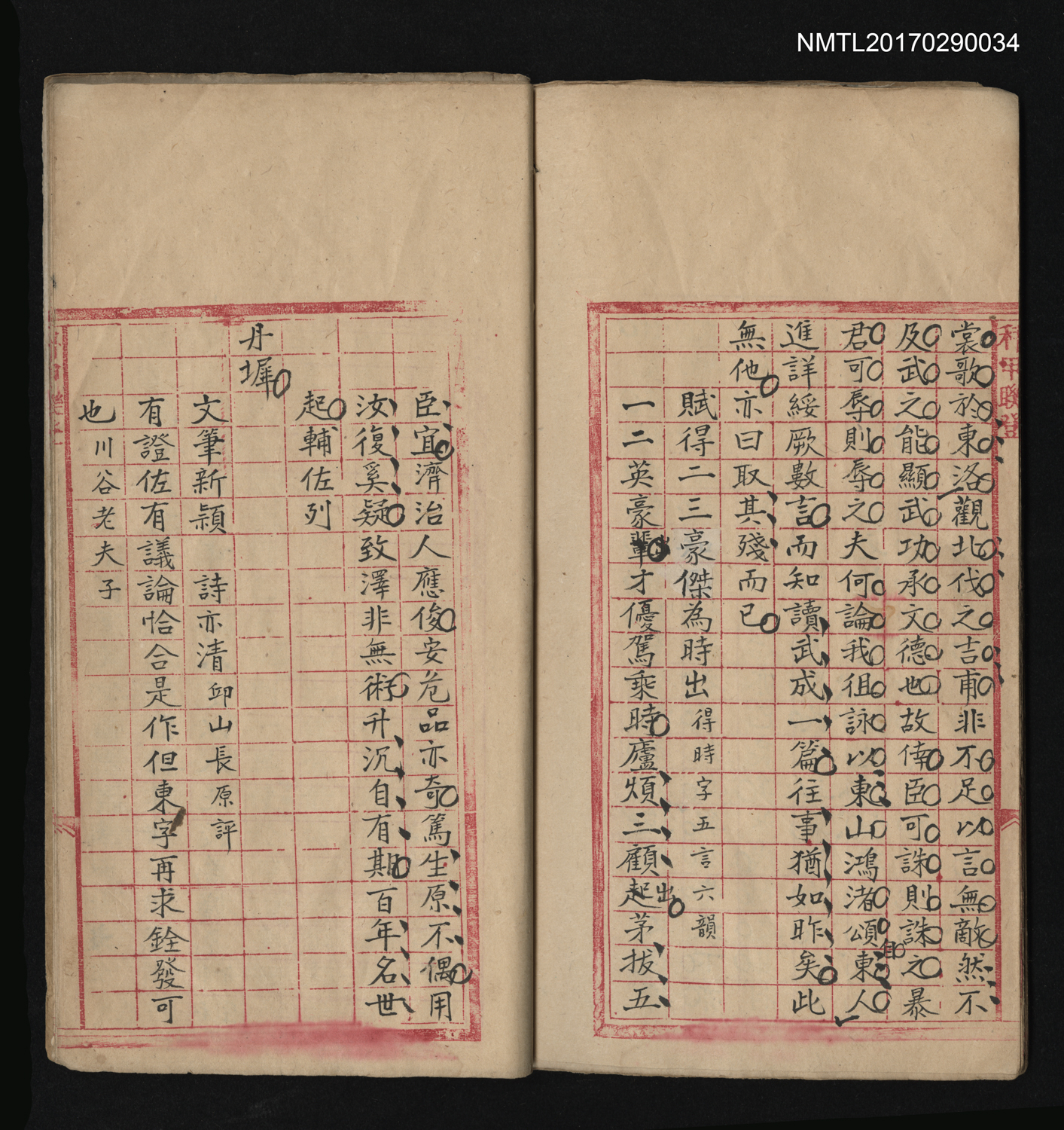

|"Record of Three Generations of Ambition," Ye Ying-hsiang, spring of Guangxu 21 (1895)|

Yeh Ying-hsiang (葉應祥) hand-copied poems and essays written by three generations of test-takers at the Academy, combining the eight-legged essays and poetry by Yeh Chao-yang (his grandfather), Yeh Kuan-kuang (his father), and himself into one large book, and adding copious annotations.

This poem's title is "Rhapsody on How Two or Three Heroes Emerge in Due Season." It follows the rhyming pattern of a five-character line with six rhyming couplets using the rhyme shi (時). At the end of the poem is a comment by Chongwen Academy headmaster Ch'iu Feng-chia: "Essay is new and original, poem is also excellent." Yeh Ying-hsiang (given name Yeh Kuo-chen, pen names Chian-chiao (嵌樵) and Jui Chun Yuan (醉春園)) was a friend of Lien Heng and a native of Tainan.

NMTL20170290034 / Donated by the family of Huang Tien-Ch'üan

5.

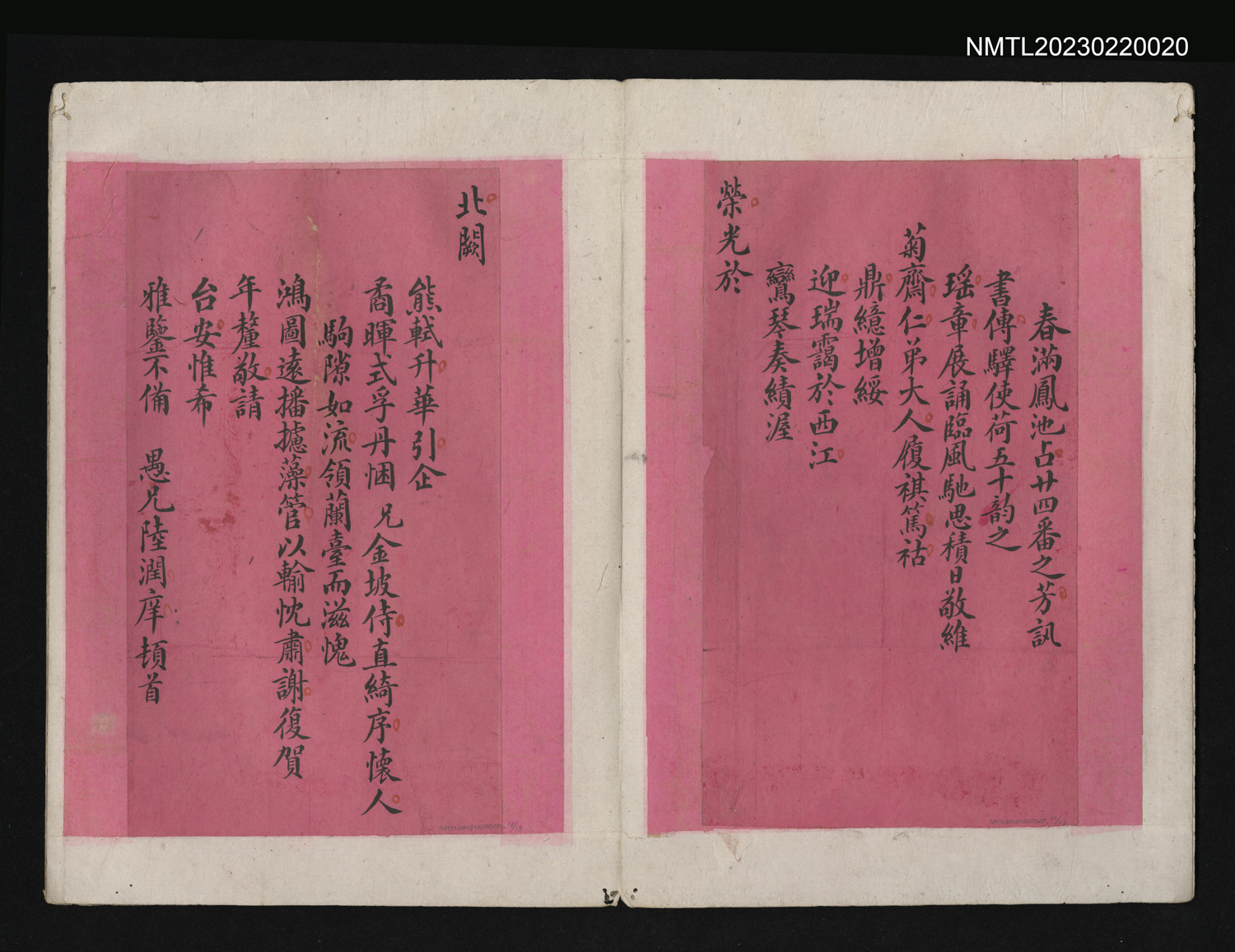

|Letter from Lu Run-hsiang to Chu Chai, Lu Run-hsiang, date unknown.|

Lu Run-hsiang (陸潤庠, 1841-1915) was a zhuangyuan, a jinshi who had ranked first place on the most difficult examination—the palace-level exam. His handwriting in this letter from him to Chu Chai is extremely tidy and regular. To pass the dianshi (palace-level) exam and become a jinshi, a scholar had to write an essay of about two thousand characters, with precisely twenty characters per line. Corrections were not allowed, and immaculate handwriting was a baseline requirement. The characters are written in an official style of regular script, reflecting the seriousness and discipline which high-level Qing dynasty officials valued in their writing.

NMTL20230220020 / Unknown donor

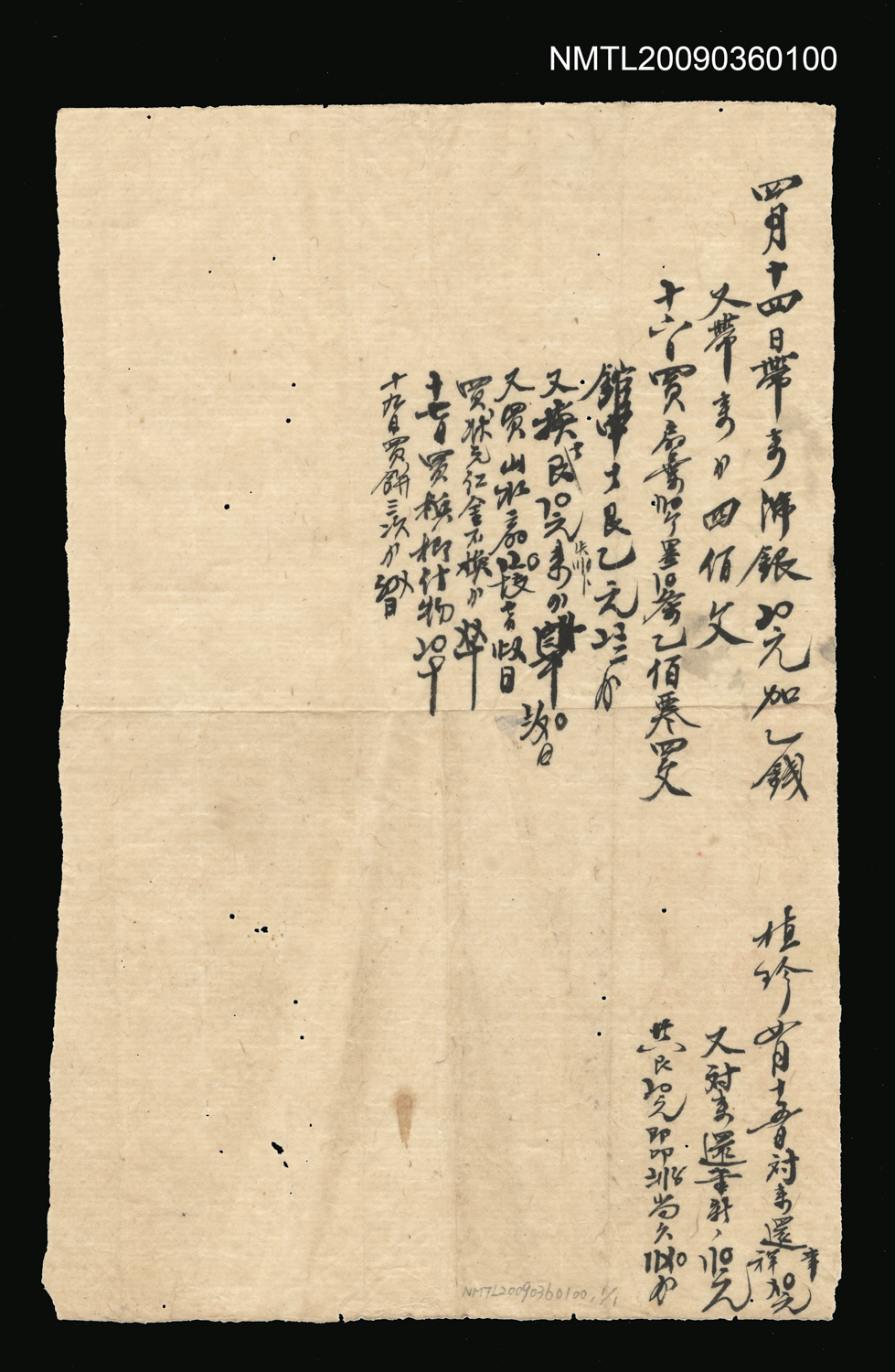

|Scholar's List of Everyday Expenses during Test Preparation, unknown author, Guangxu era (1875-1908)|

This note records the daily expenses of a scholar preparing for the imperial examinations during the late Qing dynasty. His purchases included blank fan leaves, ink sticks, fans painted with landscapes, red paper, jinbuhuan (a type of cheap paper), betel nuts, a few odds and ends, and some pastries. Total income and expenses are also recorded, along with outstanding debts. He uses Suzhou numerals (a kind of shorthand) and traditional symbols to inscribe numbers and make them easier to calculate.

This note shows us a scholar's economic situation during the late Qing in Taiwan, and gives us insight into what everyday common purchases were.

NMTL20090360100 / Donated by Chairman Chen Chung-kuang, Chen Cheng-po Cultural Foundation.

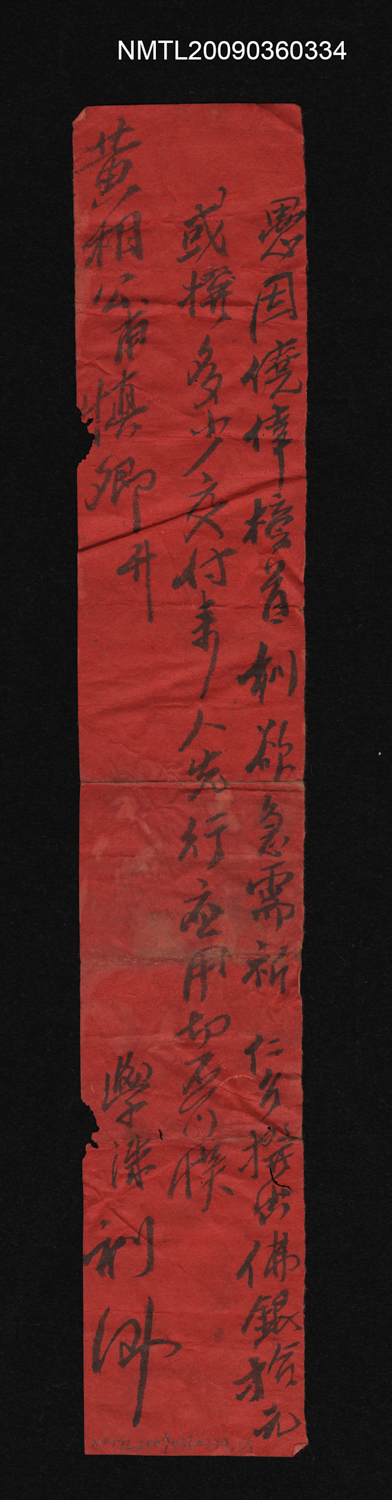

|Debt Memo, Chen Shou-yu, Guangxu era (1875-1908)|

"I have been fortunate enough to be ranked first, and am now in urgent need of funds. I humbly beseech Your Excellency to disburse without delay ten silver coins, or however many you see fit, that I may use. To Master Huang Shen-qing ○ First from Hsue Zhu"

We can guess that Chen Shou-yu wrote this letter to Huang Shen-qing after passing the entry-level examination, asking to borrow money. The urgent need for funds may have been to provide a thank-you payment to the testing examiner, or to have his bright-red calling cards printed, so that he could make formal visits and leave a name card, as etiquette demanded. "Hsue Zhu" is presumably Chen Shou-yu's given name. "First from Hsue Zhu" means that this is his first letter to Huang. This memo gives us a picture of the actual economic reality and etiquette norms surrounding the imperial examinations and the social interactions of testing scholars.

NMTL20090360334 / Donated by Chairman Chen Chung-kuang, Chen Cheng-po Cultural Foundation

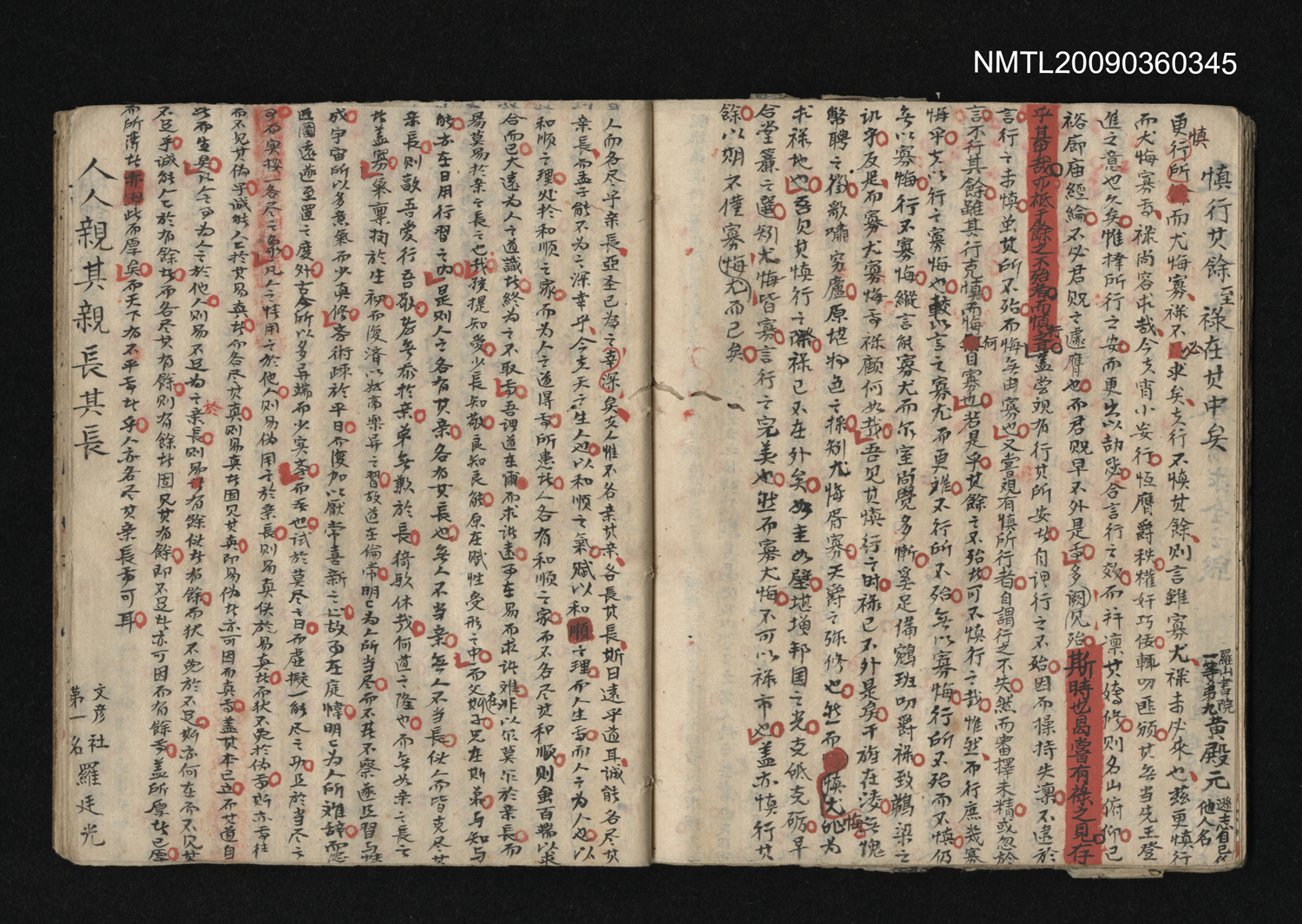

|Chuang Ke (At-home Practice), unknown author, Guangxu era (1875-1908)|

Writings from a scholar's test preparations. A chuang ke was a lesson given in the scholar's study room. This assignment was to transcribe a masterpiece eight-legged essay as practice. The prompt is "Act cautiously to minimize regrettable actions; few mistakes in speech and few regrets in action is the way to wealth and position," from "Practice of Government" in the Analects of Confucius. This essay by Huang Dian-yuan received a grade of "first class" (the minimum passing grade), and ranked ninth place at the Luoshan Academy. The test paper is only about the width of a hand. The sentences separated by circles of crimson ink and the red paper used for corrections show the meticulous approach students took to their arduous studies.

NMTL20090360344, NMTL20090360345 / Donated by Chairman Chen Chung-kuang, Chen Cheng-po Cultural Foundation

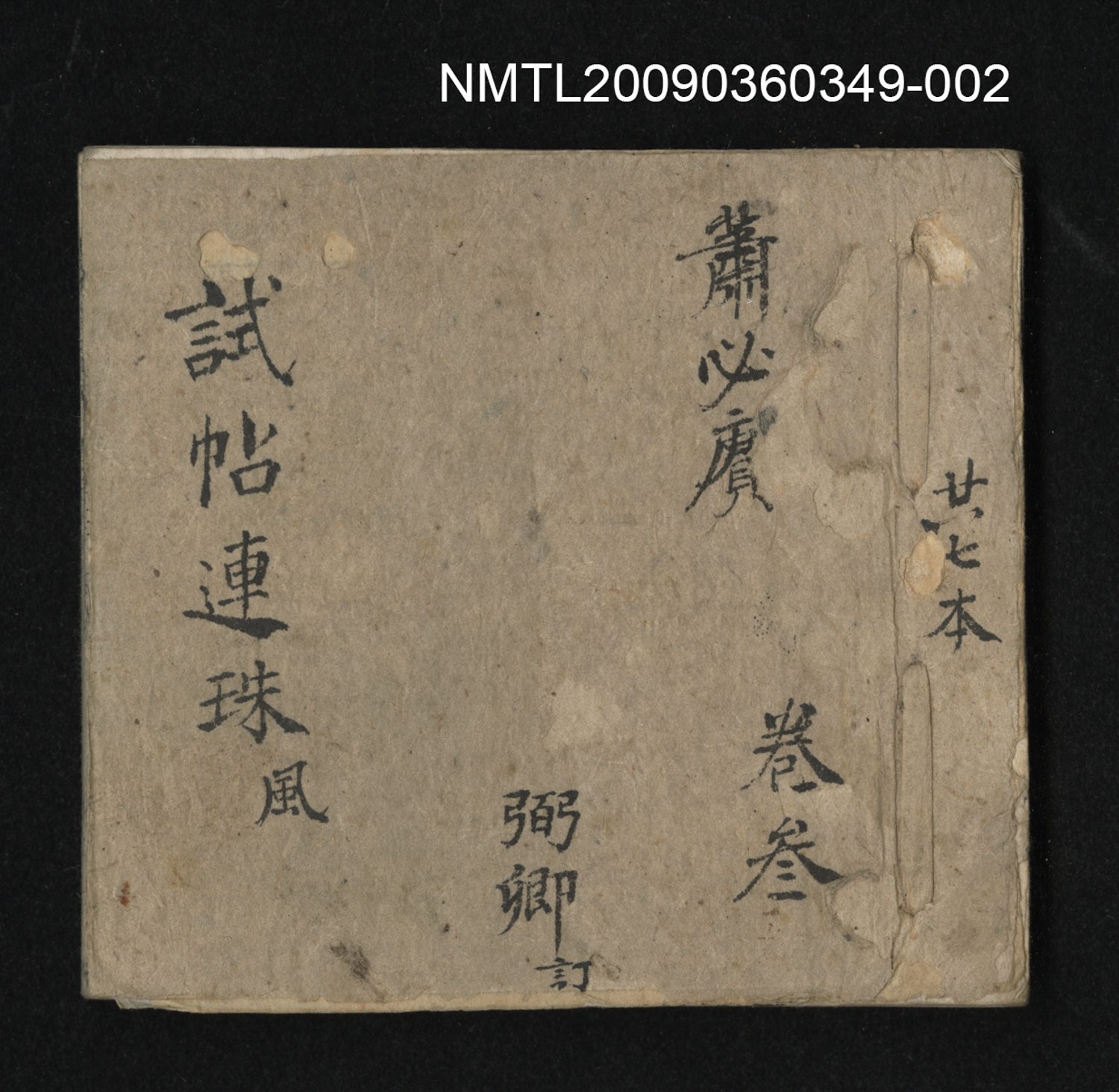

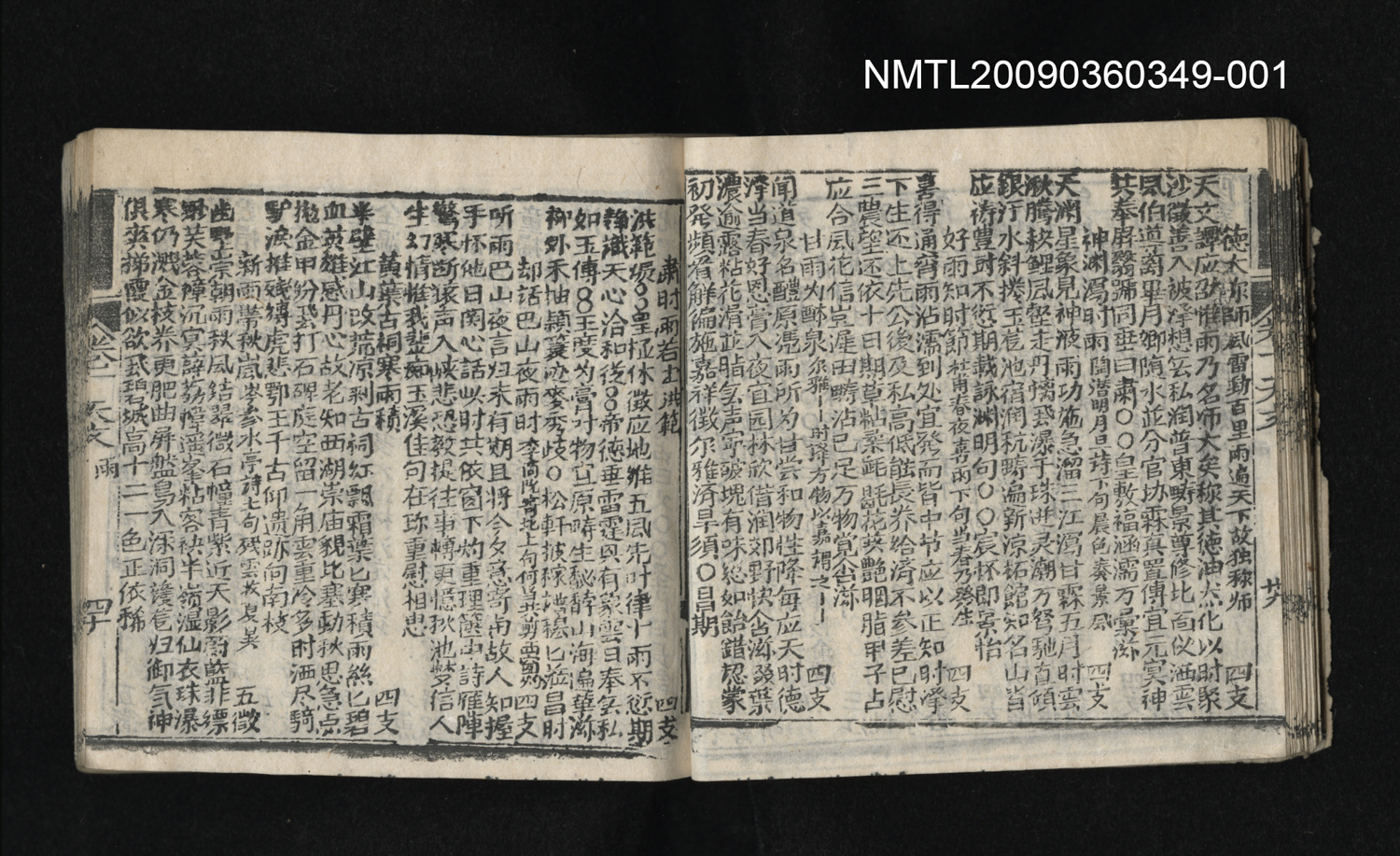

|A String of Exam Poems, unknown author, Guangxu era (1875-1908)|

A printed reference book for exam preparation. Each volume of this textbook takes its name from the characters of a line by Song dynasty poet Cheng Hao (程顥): Yun tan feng qing jin wu tian (Clouds are light and the wind is gentle around noon). This, the second volume, is thus titled Tan (light). Its content is arranged according to rhyming scheme.

It is open to "four zhi rhymes," a category defined by traditional rime tables. One of the lines is "Good rain knows when the time is right," which comes from Tang dynasty poet Du Fu's “Happy Rainy on a Spring Night." The student's poem on the test had to be a lüshi (eight-line poem) of five characters per line, and the student had to use the poem prompt as the second line.

NMTL20090360349 / Donated by Chairman Chen Chung-kuang, Chen Cheng-po Cultural Foundation

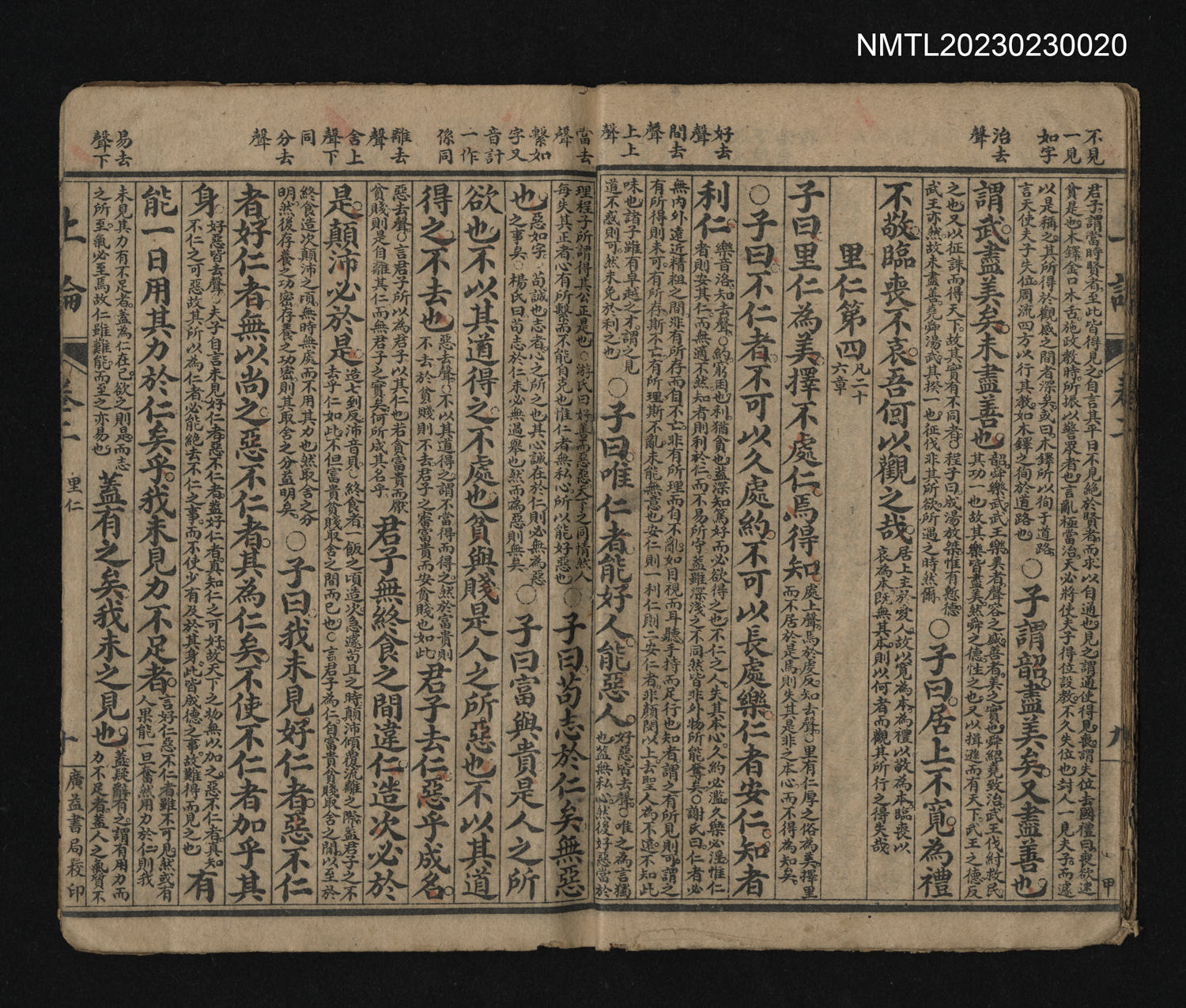

|High-grade Printing of the Four Books with Annotations, Guang-yi Bookstore, published 1915|

This printed reference book contains text from the Analects in large characters, with annotations in small characters. It is open to the chapter "Living in Brotherliness,"

where Shih Lung-wen's test question came from.

The essay questions and poem prompts for both the provincial- and metropolitan-level exams were taken from the Four Classics (the Analects of Confucius, Mencius, Doctrine of the Mean, and Great Learning); therefore, they were also typical test prep material and early traditional education. Written on the title page of this book is "Read by Cheng Jung-wei," meaning it was probably a textbook used by Cheng Jung-wei while he was being taught by Cheng Chia-chen.

NMTL20230230020 / Donated by Zi Xia Tang

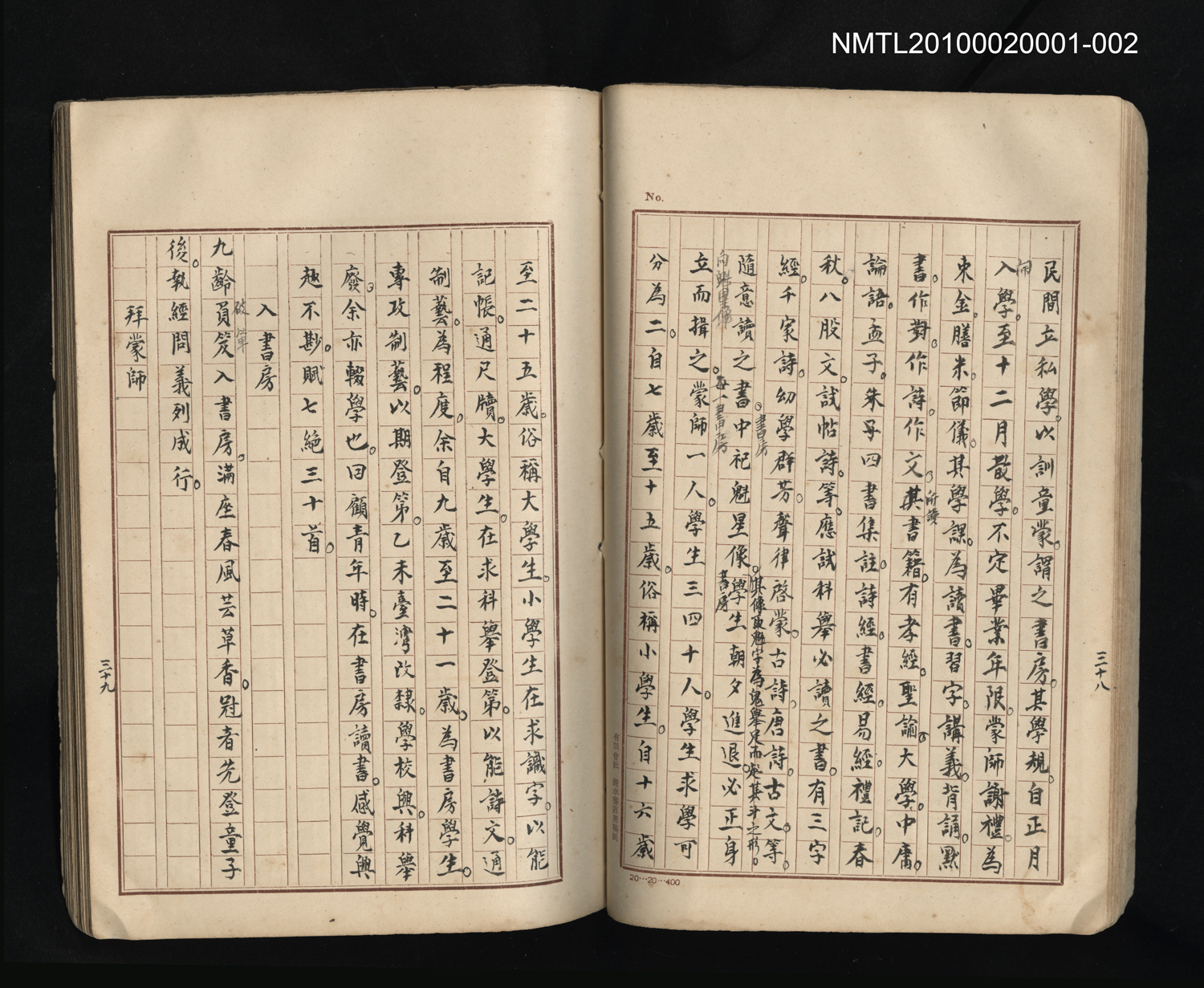

|Manuscript of Poetry by Qing-yuan, Huang Chun-ching, Japanese colonial era|

This manuscript contains a series of poems titled "Thirty Poems on the Study, with Preface," describing the poet's experiences of learning in the study room as a small child. At age seven, students became xiao xuesheng (little students), and studied reading and writing of characters and the basics of letter-writing. At the age of sixteen, they became da xuesheng (big students), and learned the principles of poetry and eight-legged essays in preparation for the examinations.

The poems reflect the days of respect for hierarchy and recitation of the Four Books in the study, along with the overall process of traditional education, study, and preparation for exams. Huang Chun-ching, whose pen name was Qing-yuan Laoren in his later years, was a member of the Ying Poetry Society and the Osmandus Pavilion Poetry Society.

NMTL20100020001-002 / Donated by Huang Te-shih.